Over the past 10 years there has been increasing awareness of the importance of promoting good mental health in South Africa. Most of the mental health awareness campaigns have been around depression, suicidal thoughts and suicide, and alcohol abuse.

Important and often overlooked forms of poor mental health are anxiety disorders. The most recent estimates of anxiety disorders in South Africa are from a 2009 nationally representative study. Anxiety disorders were the most common form of poor mental health reported by South Africans in the research. More than 8% reported anxiety disorder in the past year. Anxiety disorders include agoraphobia, which is the fear of places or situations that may cause embarrassment, as well as panic attacks. A broader form of anxiety is generalised anxiety disorder. It manifests itself as ongoing generalised worry.

This worry can be about many things – from money to how to provide for children and hopes for the future. Such generalised anxiety is associated with increased substance misuse, greater risk of acquiring HIV, as well as other mental health disorders. It may also reduce people’s economic well-being through limiting their ability to look for work, or go out and work.

Studies globally have broadly identified two main structural drivers of anxiety: poverty and violence.

In South Africa half of adults are living below the poverty line, defined as earning an income of less than R1,183 per month. Similarly, experiences of violence in childhood and later life are common. A study among 15-17-year olds found that 10% of boys and 15% of girls had experienced sexual violence in their lifetime. Violence and injuries are the second leading cause of lost disability-adjusted life years in South Africa.

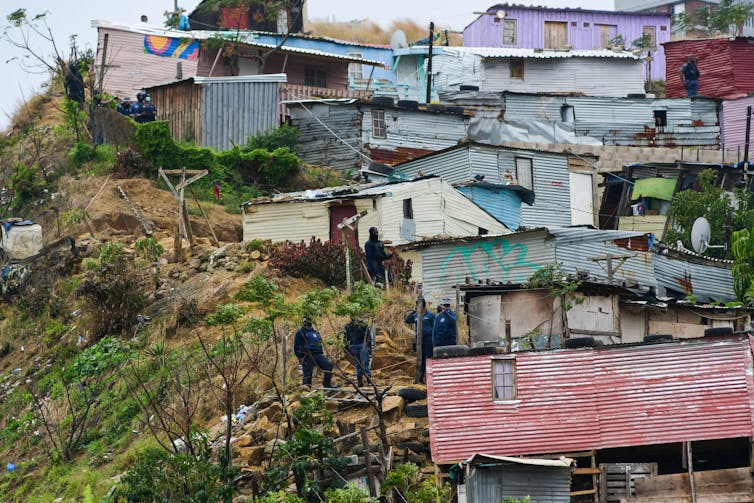

Yet the challenges of poverty, violence and chronic stress experienced by many South Africans daily and for many years are not uniform. Young people, particularly those living in the challenging contexts of urban informal settlements, may be more at risk of experiencing generalised anxiety disorder. This is because poverty and community violence are more common in these spaces than in other communities.

Few studies look at anxiety. But it remains the most common form of mental health disorder in South Africa.

Understanding the causes is important for starting to understand how to address generalised anxiety disorders. In our recent research we spoke to young people living in informal settlements in eThekwini Municipality, in KwaZulu-Natal. We asked them about their symptoms of anxiety, as well as potential risk factors for anxiety. These included abuse in childhood, interpersonal violence, food insecurity and stress related to poverty.

Symptoms of generalised anxiety disorder were higher in respondents who reported experiencing particularly extreme levels of poverty and experiencing violence. Addressing these two factors is critical for reducing poor mental health and its future impacts on individuals and potentially their children.

Anxiety in urban informal settlements

Our study was conducted in 2018. The study participants were young women and men (ages 18-30) who were already part of an intervention trial called Stepping Stones and Creating Futures. This intervention was run by the South African Medical Research Council and Project Empower, and sought to reduce poverty and violence among young people living in urban informal settlements.

We asked the respondents (488 women and 505 men) about their own experiences of symptoms related to generalised anxiety disorder. These are symptoms such as feeling nervous, not being able to stop worrying and being restless. In our study we found a high rate of women and men reporting moderate or severe symptoms of generalised anxiety disorder – 18.6% and 19.6%, respectively – as assessed through seven questions which comprised the Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7 Scale.

We asked women and men a range of questions about their experiences of poverty, violence and stress. We also looked at multiple potential risk factors for anxiety. Women with more severe symptoms of generalised anxiety disorder, as compared to those with few symptoms, were more likely to have stolen because of hunger in the past month, and be stressed about lack of work. They were also likely to have experienced more adverse events such as witnessing the death of someone or being robbed at knife or gunpoint, and to have experienced violence from a partner in the past year.

For men, a similar pattern to women was seen. More severe generalised anxiety disorder symptoms were associated with poverty and experience of violence. Specifically, men with more anxiety symptoms, as compared to those with fewer symptoms, had stolen in the past month because of hunger, reported more adverse experiences as children, and had more adverse experiences in adulthood.

Addressing anxiety in South Africa

Our findings show how poverty, experiences of violence and adverse events are key contributing factors for generalised anxiety disorder among young people living in urban informal settlements.

South Africa must address the wider structural drivers of poor mental health, specifically poverty, unemployment and violence. It is the only way to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, and specifically Goal 3.4, which emphasises the need to promote mental health and well-being.![]()

Andrew Gibbs, Senior specialist scientist: Gender and Health Research Unit, Medical Research Council, South African Medical Research Council

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.