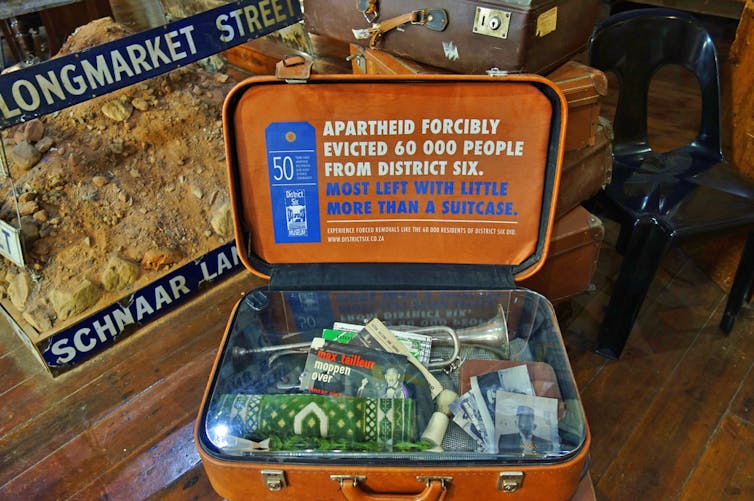

Today’s gang violence on the Cape Flats can’t be divorced from Cape Town’s history of forced removals.

EQRoy/Shutterstock/Editorial use only

When the apartheid government decided to evict people it called Coloured from Cape Town’s inner city, it set off a chain reaction that now requires military intervention.

More than 50 years on from the mass evictions that drove anyone who wasn’t white from the city centre, the South African National Defence Force has moved in to guard the areas known collectively as the Cape Flats. It was to these places that Coloured people were pushed by the Group Areas Act. So it’s necessary to look to history – which I’ve explored in a number of my books, most recently Gang Town – as violence in suburbs far from the city centre escalates.

Given the framework within which removals under the Group Areas Act took place in Cape Town, a social disaster was inevitable. As the familiar social landmarks in the closely grained working-class communities of the old city were ripped up, a whole culture began to disintegrate.

Networks of kin, friendship, neighbourhood and work were destroyed. The streets, houses and corner shops that also formed networks were torn away. With this destruction the mixture of rights and obligations, intimacies and distances, solidarity, local loyalties and traditions that bound established communities dissipated.

Above all, what the Group Areas Act’s inroads into the culture of the older districts fundamentally disturbed was the organisation and role of the working-class family. One of the major problems that arose from all this was the collapse of social control over the youth. One of the greatest complaints about Group Areas removals was that individual families rather than whole neighbourhoods were moved to the Cape Flats.

Amid these complex developments and realities, gangs emerged. There had been smaller, less hierarchical and organised gangs in areas like District Six from which people were forcibly removed. But harsh conditions on the Cape Flats saw much fiercer gangs forming and increasing use of knives and, later, handguns.

Isolation and fear

The first effect of the removals into the high-rise schemes on the Cape Flats was to destroy the way the street, the corner shop and the shebeens in the “old” areas had provided the residents with a great measure of communal space. The new areas contained only the privatised space of small, nuclear family units.

These were stacked on top of each other in total isolation, juxtaposed with the totally public space surrounding them – a space that lacked any of the informal social controls generated by their former neighbourhoods. A key control was that houses in the old areas had verandas where older people would sit and informally police the streets. On the Cape Flats you were either behind a door or on the street.

The destruction of the neighbourhood street also blew out the candle of household production, craft industries and services. The result was a gradual polarisation of the labour force into those with more specialised, skilled or better paid jobs; those with the dead-end, low-paid jobs; and the unemployed.

As the new housing pattern dispersed the kinship network, so the isolated family could no longer call on the resources of the extended family or the neighbourhood. The nuclear family itself became the sole focus of solidarity.

This meant that problems tended to be bottled up within the immediate interpersonal context that produced them. At the same time, family relationships gathered a new intensity to compensate for the diversity of relationships previously generated through neighbours and wider kinship ties.

Pressures gradually built up, which many newly nuclear families were unable to deal with. The working-class household was thus not only isolated from the outside, but also undermined from within. The main, and understandable, product of this isolation was fear: fear of neighbours, of unknown people, of gangs and of the strange dynamics of the new environment.

These pressures weighed heavily on the house-bound mothers. The street was no longer a safe place for children to play in and there were no longer neighbours or kin to supervise them. The only play-space that felt safe was “the home”, the small flat. As stresses began to build up within the nuclear family, what had once been a base for support and security now tended to become a battleground, a major focus of all the anxieties created by the disorganisation of community.

One route out of the claustrophobic tensions of family life was the use of alcohol and drugs. This became the standard path of many men. Children were shaken loose in different ways. One way was into early sexual relationships and perhaps marriage.

Another was into the fierce youth subcultures on the streets which became ritualised in the violent youth-gang culture, reinforcing the neighbourhood climate of fear. The situation was to be compounded by rising unemployment at the younger end of a potential labour force and the consolidation of illegal markets that required “soldiers” to protect.

What these gangs did in order to survive in the face of tremendous odds was to rebuild the lost organisation and domestic economy in the new housing-estates. This time, however, their customers and they themselves were often also their victims.

Then came 1994 and the newly elected African National Congress (ANC) government inherited, in Cape Town, a working class that was like a routed, scattered army, dotted in confusion about the land of their birth.

The ultimate losers in this type of claustrophobic atmosphere are the working-class families. For those scattered across the Cape Flats, the emotional brutality dealt out to them in the name of rational urban planning has been incalculable. The only defence the young people have had has been to build something coherent out of the one thing they had left – each other.

Too little too late

Bringing soldiers onto the Cape Flats is too little and too late to unscramble the political omelette. What’s needed is not repression but contrition, better intelligence and the rebuilding of damaged communities whiplashed by gunfire.

Don Pinnock, Research fellow, criminologist, University of Cape Town

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.