Calls for help at Chicago’s Cook County jail, where hundreds of inmates and staff have COVID-19, April 9, 2020.

Kamil Krzaczynski/AFP via Getty Images

Jails and prisons around the United States are considering freeing some of their inmates for fear that correctional facilities will become epicenters in the coronavirus pandemic.

COVID-19 has infected hundreds of prisoners and staff in city jails, state prisons and federal prisons.

New York, California and Ohio were among the first to release incarcerated people. Other states have followed, saying it is the only way to protect prisoners, correctional workers, their families and the broader community.

Jails and prisons often lack basic hygiene products, have minimal health care services and are overcrowded. Social distancing is nearly impossible except in solitary confinement, but that poses its own dangers to mental and physical health.

As a prison scholar, I recognize a sad irony in this public health problem: The United States’ very first prisons were actually designed to avoid the spread of infectious disease.

Early American jails

The first U.S. prisons emerged in reaction to the overcrowded, violent, disease-infested jails of the colonial era.

Prisons as we understand them today – places of long-term confinement as a punishment for crime – are relatively new developments. In the U.S. they came about in the 1780s and 1790s, after the American Revolution.

Previously, American colonies under British control relied on execution and corporal punishments.

Jails in America and England during that period were not themselves places of punishment. They were just holding tanks. Debtors were jailed until they paid their debts. Vagrants were jailed until they found work. Accused criminals were jailed while awaiting trial, and convicted criminals were jailed while awaiting punishment or until they paid their court fines.

The British penal reformer John Howard visiting a prison.

Wikipedia, CC BY-NC

Consequently, early American jails were not designed for long detentions, even if people sometimes stayed for months or longer.

The physical structure of these unregulated local facilities – often run by sheriffs or private citizens who charged room and board fees – varied. Jail could be a spare room in a roadside inn, a stone building with barred windows or a subterranean dungeon.

Fear of disease

Disease, violence and exploitation were rampant in these squalid American colonial and British jails.

John Howard, a British aristocrat whose ideas influenced American penal reformers, became concerned about living conditions in these “abode[s] of wickedness, disease, and misery” when he became a sheriff. In a 1777 book, Howard recounts smelling vinegar, a common disinfectant of the era, to protect against the revolting smell of the jails he visited.

Howard warned readers that jails spread disease not only among inmates but also beyond, into society. He recalled the so-called Black Assize of 1577, in which prisoners awaiting trial were brought from jail to an Oxford courthouse and “within forty hours” more than 300 people who had been at court were dead from “gaol fever” – what we now call typhus.

He also wrote of infected prisoners who, once released, brought diseases from jail into their communities, killing scores.

Disease also shaped Howard’s understanding of how criminality spread.

He described how young “innocents” – the children of people jailed for debt or those awaiting trial for a petty offense – were seduced by dashing bandits’ stories of crime and adventure. Thus “infected,” they went on to become criminals themselves.

America’s first prisons

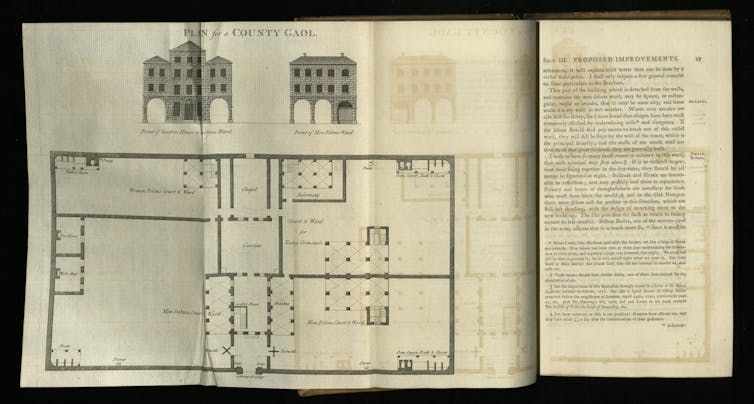

Howard’s ideas, particularly the realization that jails posed a threat to the public, were brought to the U.S. by Philadelphia reformers like Benjamin Rush, a physician and signer of the Declaration of Independence.

Following the recommendations in Howard’s book, American penal reformers pushed for new jails designed to ward off disease, crime and immorality of all kinds.

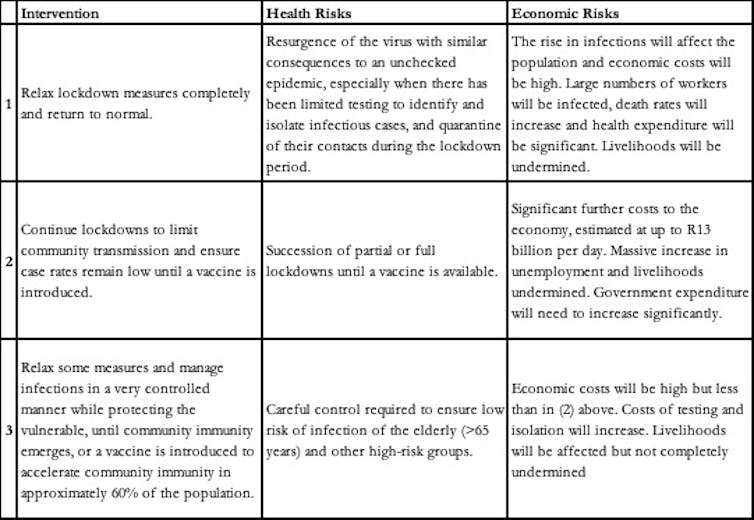

Howard envisioned new facilities that would be well ventilated and cleaned daily. Clothing and bedding should be changed weekly. There would even be an infirmary staffed by “an experienced surgeon” who would update authorities on the state of prisoner health.

Howard’s plan for a ‘County Gaol’

The Royal Collection Trust

American reformers followed Howard’s advice that “women-felons” should be kept “quite separate from the men: and young criminals from old and hardened offenders.” Debtors, too, should be kept “totally separate” from the “felons.”

Prisoners should be separated from one another, ideally in cells. Crowding should be avoided. All this would prevent the spread of disease and enable the prisoners’ repentance – and thus their rehabilitation.

Using Howard’s book as their guide, Rush and his colleagues transformed Philadelphia’s aging and overcrowded Walnut Street Jail into one of the country’s first state prisons by 1794. The Walnut Street Prison model was soon adopted nationwide.

Philadelphia’s Walnut Street Jail.

Wikipedia Commons

Health care in prisons today

The U.S. long ago departed from the idea that prisons should protect both prisoners and society.

The biggest shift in prison health care occurred between the 1970s and today – the era of mass incarceration. The U.S. incarceration rate doubled between 1974 to 1985 and then doubled again by 1995. The number of people in American prisons peaked in 2010, at 1.5 million. It has declined slightly since, but the U.S. still has the world’s largest incarcerated population.

Prison building, although unprecedented in scale, has not kept pace. Many corrections facilities in the U.S. are dangerously overcrowded.

A gymnasium turned dorm at the California Institution for Men in Chino, May 24, 2011.

Ann Johansson/Corbis via Getty Images

In 1993, 40 states were under court orders to reduce overcrowding or otherwise resolve unconstitutional prison conditions. Many more lawsuits followed. Still, the prison population grew.

One consequence of overcrowding is that prison officials have a difficult time providing adequate health care.

In 2011 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that overcrowding undermined health care in California’s prisons, causing avoidable deaths. The justices upheld a lower court’s finding that this caused an “unconscionable degree of suffering” in violation of the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment.

Amid a worldwide pandemic, such conditions are treacherous. Some of the worst COVID-19 outbreaks in U.S. prisons and jails are in places – like Louisiana and Chicago – whose prison health systems have been ruled unconstitutionally inadequate.

Criminologists and advocates say many more people should be released from jails and prison, even some convicted of violent crimes if they have underlying health conditions.

Opponents of coronavirus-related releases, including state officials in Louisiana, contend that the move poses a high risk to public safety. And victims of violent crimes complain that they have not been notified when their victimizers are set to be released.

The decision to release prisoners cannot be made lightly. But arguments against it discount a reality recognized over two centuries ago: The health of prisoners and communities are inextricably linked.

Coronavirus confirms that prison walls do not, in fact, separate the welfare of those on the inside from those on the outside.

[You need to understand the coronavirus pandemic, and we can help. Read The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Ashley Rubin, Assistant Professor of Sociology, University of Hawaii

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.