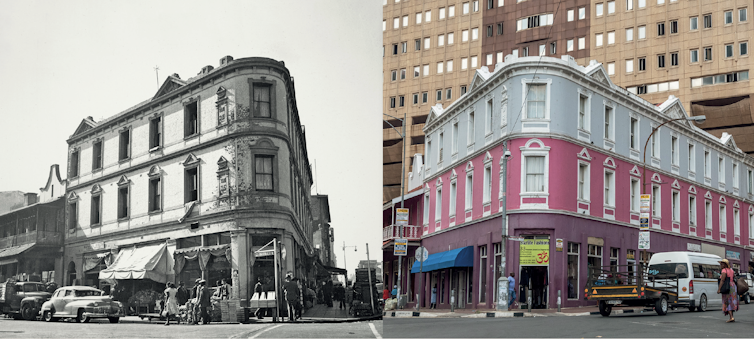

A significant number of South Africans can’t find jobs and scrounge for a living on the sidelines of the economy.

Shutterstock

Nearly a week has passed since South Africa’s 2018 jobs summit. The two-day gathering produced some useful agreements between the social partners: government, organised labour and business (essentially, big business).

This was the fourth jobs summit in 20 years. The frequency of attempts to find a solution to the country’s unemployment problems isn’t surprising given that South Africa has one of the highest jobless rates in the world. The unemployment rate has increased from under 22% in 2008 to the current rate of 27.2%.

But the record on delivering results has been mixed, to say the least.

The first jobs summit in the post 1994 era was held in 1998 when Nelson Mandela’s presidency was nearing its end and amid a developing country debt crisis. It achieved very little. The next one – the 2003 Growth and Development Summit – achieved significant agreements. But these were poorly monitored and implemented.

Six years later in 2009 social partners agreed on a framework to respond to the global financial crisis. In spite of the measures introduced by agreements reached at the gathering, South Africa lost nearly a million jobs.

Undoubtedly the outcome of the recent summit is positive. Job-saving elements of the 2009 agreement have been revived. There are forward-looking commitments such as finance for the black industrialist scheme and a focus on the export of manufactured products. There are initiatives for small business support, technical training and a mechanism for the absorption of graduates into the economy.

But perhaps the most important outcome was that a Presidential jobs council will be established to monitor progress.

As welcome as these developments are, the agreement doesn’t explicitly acknowledge that there might be some fundamental issues in the approach to development and job creation in South Africa. In a paper just published Brian Levy and I identify what these might be.

We argue that the implicit social compact of the 1990s laid a poor foundation for job creating growth in South Africa. Our view is that unless South Africa revisits the implicit and explicit deals struck at that time, the chances of making serious inroads into unemployment are remote.

But is South Africa in the kind of crisis as Mauritius was in 1968 and Ireland in 1988, where key social players were forced to review the social compact and work together towards a coherent developmental model? And do the social partners have strong enough leaders to arrive at suitable agreements?

These are the questions excitingly raised by the outcome of jobs summit, and should, in our view, be the preoccupation of the President’s jobs council.

The 1990s compact

An elite bargain over the country’s economic framework formed an essential part of the foundation for a democratic South Africa. The context of the bargaining process included the capitulation of the communist block, economic stagnation in most African countries, and a relentless campaign by the white South African business community for government not to intervene in the economic framework.

There was the threat of flight of capital and white citizens who were virtually monopoly owners of wealth and key economic skills and networks. What emerged was an apparently strong commitment to market-opening reforms.

The result is well known. The economic policies emphasised what was then called “getting the prices right and what we call "disciplining reforms”. This included: trade and financial liberalisation, fiscal restraint, tougher competition laws and a conservative mandate for the central bank.

Conversely, policies lacked on the side of interventionist mechanisms that were effective in some more successful developing countries. These included support for industrial innovation, cluster development and industrial policy which would have encouraged domestic investment in job creating growth.

Policy choices weren’t the only problem. Key players in the economy were pursuing new agendas as their options had broadened with the end of South Africa’s economic isolation and the repression of apartheid.

South African corporations were focused on narrowing their South African operations and spreading their activities and assets abroad. While they cast off some non-core assets, the corporations remain extraordinarily powerful.

At the same time, the trade unions used their bargaining power with government to strengthen worker rights. All labour laws had to go through the newly formed National Economic Development and Labour Council (NEDLAC) and could not go through until all parties were happy. The result was that big business, which always dominated the business delegation, agreed to labour laws that they could manage with their sophisticated human resource departments and because of the choices they could exercise. However, these laws were not all easy to implement for small and medium companies.

In addition, the reformed industrial training system was poorly designed which set back industrial training for many years.

The market opening reforms combined with the labour reforms achieved very little in the way of supporting dynamic investment and innovation. So, the elite pact that emerged reflected what powerful stakeholders were prepared to agree too – not a coherent package derived from carefully thought out trade-offs.

Compared with outcomes of more successful social pacts like Mauritius in the late 1960s and Ireland in the late 1980s, South Africa’s social compact failed. And over time commitment to the elements of the compact waned.

In a different world

In a different world, perhaps, had South African elites agreed on a clear developmental model and had they strived for suitable strategies, the outcome might have been very different. There would have been a much stronger emphasis on the more interventionist kinds of supportive industrial policies.

It’s not too late. More recently, industrial policy has formed part of the approach of government as seen in major initiatives in several sectors.

Informed analysts in South Africa are now asking “Where is growth going to come from?” Skilled people are streaming out the country as they did in Mauritius in the 1960s and in Ireland in the 1980s. Could it be that this is the moment for a coherent, developmental social compact?

Alan Hirsch, Professor and Director of The Nelson Mandela School of Public Governance, University of Cape Town

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.