A poverty index is revealing new insights about deprivation in South Africa.

Shutterstock

There’s more to understanding a country’s poverty levels than merely calculating how much or how little individuals earn. That’s why a method called the multidimensional poverty index was introduced globally in 2011.

The multidimensional poverty index reflects aggregate levels derived from a number of socioeconomic indicators. These include education, health, standard of living and labour market activity. It unveiled new insights about the nature of poverty around the world.

South Africa had been watching with interest. In 2014, Statistics South Africa adopted the multidimensional poverty index into understanding the nature of the country’s poverty. The move produced the South African multidimensional poverty index (SAMPI).

Before this, the picture of the country’s poverty was mainly informed by the money-metric approach, which examines the proportion of the population with income below the minimum level required for survival (poverty line).

The SAMPI is still a relatively new and thus developing method. With that in mind, our recently published study zoomed into Statistics South Africa’s new multidimensional approach, pointed out and addressed numerous shortcomings in the method. We were then able to develop a more granular version of SAMPI. Our version focused on smaller geographical units in South Africa, namely district municipalities, from 2001 to 2011. The aim was to identify, more clearly, the location and characteristics of the poorest individuals.

The most important finding of our study is in refinement of the SAMPI by indicator. It shows that unemployment contributed the most to SAMPI, followed by years of schooling and disability. The results indicate that the government needs to move with urgency in its efforts of boosting job creation and improving quality and access to education and healthcare.

Some good news

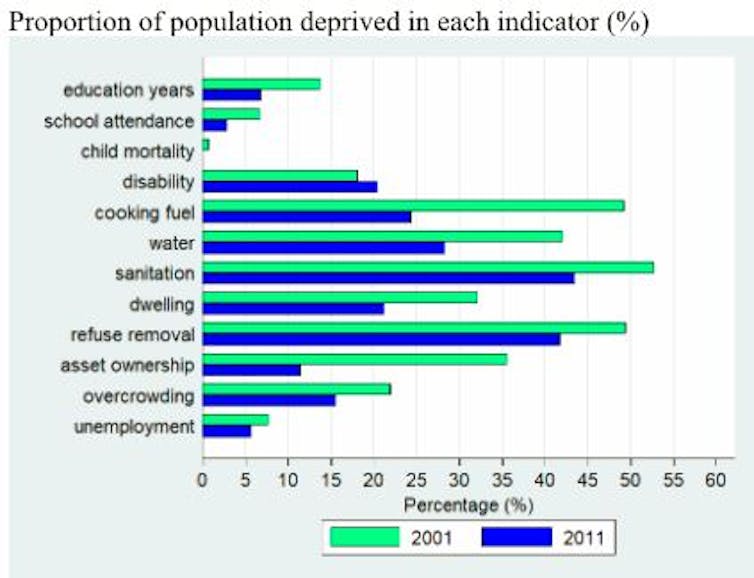

Our version of SAMPI found a generally downward trend in the proportion of deprived population for all indicators, except the disability indicator, between 2001 and 2011, as reflected in the figure below.

Proportion of population deprived in each indicator (%)

From the authors

But we also found some alarming indications. In 2011 just under half of the population still did not have access to a flush toilet and refuse removal at least once a week. These two proportions were 53% and 50% for Africans but only 1% and 9% for the white population.

We found that poverty was most severe amongst female Africans living in rural areas in the Eastern Cape, KwaZulu-Natal and Limpopo provinces. In 2011, the top five least deprived district municipalities were West Coast, Cape Winelands, Overberg, City of Johannesburg and City of Cape Town.

In contrast, Alfred Nzo a district municipality in the Eastern Cape was the most deprived district. It was followed by OR Tambo also in the Eastern Cape, uMzinyathi (KwaZulu-Natal), Harry Gwala (KwaZulu-Natal) and Chris Hani (Eastern Cape).

One encouraging finding was that the most deprived districts in 2011 were also the ones enjoying the most rapid absolute decline in the multidimensional poverty index between 2001 and 2011. This result is not surprising given the government’s effort to improve the provision of free basic services since the democratic transition.

The key drivers

It should be no surprise that unemployment contributed the most to multidimensional poverty index. South Africa’s unemployment rate has remained stubbornly high and is currently seating at 26.7%. This rate is shockingly high for the youth aged 15-29 years at 44.3%. Nearly half of the unemployed youth struggle to find the first job.

The couple of initiatives directed at addressing youth unemployment have not made a difference. These include the Employment Tax Incentives Bill or the Youth Wage Subsidy. Only time will tell if the newly introduced Youth Employment Service initiative would change the situation.

It’s been clear for a while that the South African economy changed into one that has greater demand for more educated and high skilled workers. This dynamic is not being addressed adequately. In 2017 only 53% of African job seekers aged 21-25 years completed Matric. This proportion was 83% for the white counterparts.

South Africa was ranked second from the bottom in Grade 8 Mathematics and last in Grade 8 Science mean test score in the 2015 Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study. South Africa was also ranked last in Grade 4 Reading mean test of the 2016 Progress in International Reading Literacy Study. The disappointing performance of South African learners in these tests strongly suggests the presence of poor quality education at most schools, which subsequently becomes a crucial factor that sustains and deepens poverty.

The under performance of learners has to do with a wide range of factors. These include family socio-economic status, access to basic learning resources such as textbooks and school facilities, teacher quality, remuneration and absenteeism, and even quality of preschool education. All these areas should receive urgent policy attention.

Data from the 2016 General Household Survey indicated that when feeling ill, only 55% of Coloureds and 60% of Africans consulted healthcare workers (compared to 80% in the case of Indians and whites). Also, about 20% of African-headed households living in poorer provinces, such as Limpopo, needed more than half an hour to visit the nearest health facility.

And the proportion of households claiming they were very satisfied with the quality of healthcare services received was relatively low for certain demographic groups. It was 58% for African-headed households but 86% for white-headed households. It was 55% in KwaZulu-Natal, North West and Northern Cape but nearly 70% in Western Cape.

A better understanding of public healthcare issues in terms of access and quality is needed, especially given imminent major health reforms via the proposed National Health Insurance.

Room for improving the SAMPI further

The SAMPI has revealed new and useful insights into the nature of South African poverty. These can be used by policy makers to come up with more informed interventions. And our version has produced an even more refined understanding. But there is still room to improve the SAMPI further by considering other non-money-metric poverty indicators like transport assets, financial assets, physical and social isolation and vulnerability and helplessness.

Derek Yu, Associate Professor, Economics, University of the Western Cape

This article was originally published on The Conversation.