Jacob Zuma, president of South Africa. There are renewed calls for citizens to directly elect their president and other representatives.

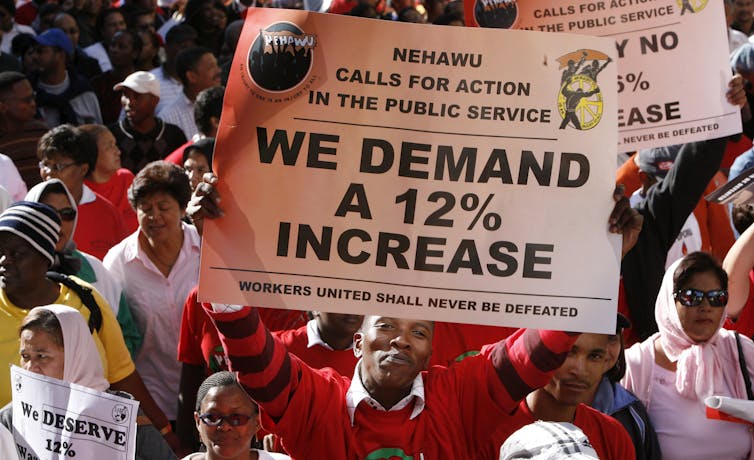

Reuters/Sumaya Hisham

Within a short time, the 4000 odd delegates to South Africa’s governing African National Congress’s 54th National Conference will elect a new party leader. In turn – save death, disaster or unlikely electoral defeat – a parliament stuffed with an ANC majority will at some point elect that leader as the new President of South Africa. The expectation is that this will be Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma or Cyril Ramaphosa. But, if the ANC elects a pig, the ANC parliamentary majority will vote for the pig.

Although it is by no means unusual for parliaments to elect countries’ political leaders, there is widespread complaint in South Africa that it is the small ANC elite which attends the conference that effectively selects the next president of the country. This, it is said by many, is undemocratic.

Two main reasons are cited. First, ANC electoral procedures are deeply corrupted by money changing hands, personal ambition and factionalism. Second, it should be the people, not the party, which should be charged with electing the country’s leader.

It is therefore of considerable interest that, rather than emanating from civil society or another political party, the proposal has been made by the ANC’s Gauteng provincial conference that consideration should be given to ordinary voters voting directly for presidents, premiers and mayors. This is of particular interest given that Gauteng is one of the ANC’s most powerful provinces, and at the same time, one which is often at odds with the party’s current leadership.

The proposal that the state president, provincial premiers and mayors be directly elected is a most welcome one, as there is much need to consider the quality of South Africa’s democracy, and to encourage public participation in decision-making. However, direct election of such offices simultaneously holds its risks.

The electoral reform debate

The debate about electoral reform in post-1994 South Africa has largely focused on the system used to elect MPs and their counterparts in the country’s nine provinces. The standard argument for a change was captured succinctly by ANC dissident and Umkhonto we Sizwe veteran Omry Makgoale:

When will we wake up and reform our crooked electoral system?

The argument is that the list proportional representation system results in the election of MPs who are accountable to party bosses rather than voters. Such an outcome is rendered more certain by the fact that South Africa’s constitution lays down that MPs or provincial legislature representatives who leave or are ejected from their parties lose their seat in the relevant legislature, plus the handy salary that goes with it. To continue with the animalistic referencing, parties’ elected representatives become sheep, devoid of any capacity for independence.

Presidential hopeful Nkosazana Dlamini-ZumaChairperson.

Reuters/Francois Lenoir

Such critiques often suggest (very sensibly) that the electoral system should become a mixed one which combines proportionality of outcomes with the direct election of representatives from constituencies. This was recommended in 2002 by the Van Zyl Slabbert Commission on electoral reform. But there has been relatively little debate about whether the President and premiers should be directly elected.

The survey conducted on behalf of the Van Zyl Slabbert Commission indicated that 63% of respondents would have liked to vote for the president directly. This level of preference was pretty much the same across all racial groups. Given the disastrous nature of the Zuma presidency, it is very possible that the preference for direct election would be considerably higher if the issue was put to survey respondents today.

Virtue of direction election

The virtue of the direct election of key political leaders is said to be that it renders them directly accountable to voters rather than to their political parties. On the face of it, it is an attractive argument, and it is one which could usefully introduce more diversity into the South African political system.

If they wanted to maximise their vote, parties would have to look at the qualities of their candidates, and ask themselves whether they would appeal to the electorate as a whole. (On this reckoning, it is a dead cert that Cyril Ramaphosa would streak home and dry, rather than, as under the ANC’s present system, running neck and neck with his chief rival, whose popular appeal is that of a wet fish). This would mean that candidates would end up openly campaigning for the leadership, dispensing with the ANC’s absurd pretence that individuals should not demonstrate political ambition.

There is also the possibility that voters would elect a president from a party other than the one which enjoys a majority in the National Assembly.

Would direct election of the president, premiers and mayors be a good idea? And, if so, what system should be adopted?

The second question is easily answered. To avoid the election of a president who gains less than 50% of a popular vote but more than any other candidate, provision would wisely be made for a second round of a presidential election in which the top two candidates engage in a run off.

A good idea?

So would direction elections be a good idea?

Parliamentary systems work well because they devolve the election of prime ministers to the legislature. On the continent, countries that inherited a parliamentary system from Britain subsequently opted for elective presidencies.

The results are not unambiguously encouraging.

South African Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa.

GCIS

In Kenya and Zambia, for instance, the direct election of presidents may have weakened the link between legislatures and executives. This has allowed executives to trample over legislatures, and for leaders to claim a legitimacy separate from that of their party. Presidents from Daniel Arap Moi through to Uhuru Kenyatta in Kenya and from Frederick Chiluba through to Edgar Lungu in Zambia have all proved exceedingly authoritarian.

It follows that changing the South African system to allow for direct election would require the country to look carefully at how a directly elected president should be rendered accountable to parliament. Would the change enhance the accountability of the government by empowering MPs, or would it render them increasingly irrelevant?

Dangers of an all-powerful president

It is also worth recalling that there is now much greater awareness about how much power is concentrated in the Presidency, in a way, it would seem, that the makers of the country’s constitution did not intend. Under Zuma, the presidency has a direct say in far too much, such as the right to appoint the head of a National Prosecuting Authority which might have the responsibility of calling him to legal account.

South Africans need to be wary of any change in the system which ends up making the President less – rather than more – accountable.

In any case, while there can be very good reasons for reforming an electoral system, this will not automatically result in better governance. Form can rarely trump substance. Robert Mugabe only “won” the Zimbabwean presidency in 2008 through his army and police terrorising the opposition and effectively forcing his rival, Morgan Tsvangirai, to withdraw.

Roger Southall, Professor of Sociology, University of the Witwatersrand

This article was originally published on The Conversation.