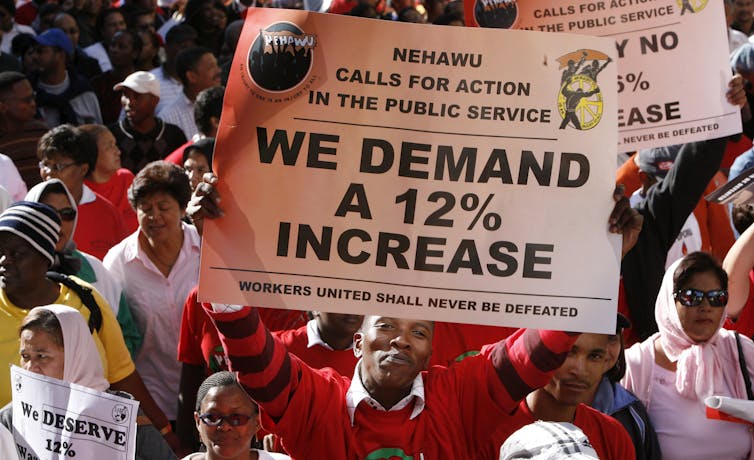

South African public sector workers march for higher pay.

Reuters/Mike Hutchings

The biggest changes to South Africa’s labour laws since 1995, shortly after the country’s first democratic elections, are currently being considered by parliament. If passed into law, they will significantly limit the hard won rights of workers to strike. In addition, details about the country’s much-heralded national minimum wage set out in the enabling legislation show that, in practice, it may be unenforceable.

The three bills include amendments to the Labour Relations Act and the Basic Conditions of Employment Act, as well as the new National Minimum Wage Bill.

If these proposed amendments become law it will be a significant defeat for workers. Taken together the legislation would roll back the hard won gains of the labour movement in South Africa and curtail the most powerful tool available to workers to improve their earnings.

The end result is likely to deepen South Africa’s vast inequalities.

The right to strike

Two of the proposed changes will affect workers’ right to strike, which is protected under South Africa’s Constitution.

First, the proposed amendments to the Labour Relations Act would introduce measures which, although designed to minimise violent strikes, would, in fact, discourage strikes in general. For example, the amendments would require trade unions to hold secret ballots to decide on strikes. By individualising the decision to strike, the secret ballot fundamentally undermines the collective nature of a strike.

Second, the proposed Labour Relations Act amendments will introduce a mechanism where strikes could be resolved through an advisory arbitration panel, which would be led by a senior commissioner of the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration (CCMA).

The problems with this are that the circumstances under which an advisory arbitration panel can be convened are very broad and, crucially, employers will have the right to request it. Meaning employers will have an easy way to resolve strikes without necessarily having to engage their workers directly or agree to any of their demands. The decision of the advisory arbitration, unless appealed, will be binding on all parties.

On top of this, trade unions can be interdicted at any time during what would be a more onerous procedure.

If passed, the amendments would make protracted strikes, such as the 2014 platinum strike, highly unlikely.

Show us the money

Details of the bill reveal a different picture of the country’s much heralded national minimum wage of R3,500 (USD$256). There will be no monthly minimum wage, only an hourly minimum wage of R20 p/h. Those that work flexible hours or part time will be unlikely to earn the R3,500, if they work under 40 hours a week. For domestic and farm workers the news is worse: farm workers will earn R18 p/h, while domestic workers will receive only R15 p/h. Only in 2020 will these workers receive the full minimum wage.

Two problems loom large in the implementation of the national minimum wage. One is compliance, the other redress.

Some sectors, including domestic work and farm work, already have minimum wages prescribed in the sectoral determination. But, non-compliance can be as high as 50%, as is the case in the agricultural sector. Based on current experience, there is no reason to think that compliance with the national minimum wage will be any different.

But, the ability of workers to get justice will become significantly more difficult.

Under the proposed amendments, the enforcement of the national minimum wage will move from the Department of Labour to the CCMA. This will make the process of seeking redress more arduous.

If a worker is being underpaid, she will have to refer her case to the CCMA. The average time for a case to reach arbitration is 60 days, but in the experience of the Casual Workers Advice Office it can take many more months.

Even if a worker eventually receives an arbitration award, many employers can simply ignore it. The next step is for the worker to have the award certified by the CCMA. If the employer still refuses to abide by the award the worker has to get a writ of execution, which is then served by a sheriff but often only after the demand for a deposit has been met. In 2016/2017, the CCMA had to assist 4,000 low-paid workers in getting a writ of execution. Many more workers often give up hope and never see through the enforcement of their arbitration award. Many more are not even aware of the CCMA remedy.

By making the CCMA the primary enforcer of the national minimum wage, the process is likely to become fraught with legal and practical difficulties, making the whole process unworkable.

What’s worse is that, to accommodate the national minimum wage, the amended Basic Conditions of Employment Act will actually roll back important rights for some workers.

Sectoral determinations do not only prescribe minimum wages but provide important protections for workers, such as provident funds. Amendments to the act will mean that the sectoral determinations will be phased out and replaced with the national minimum wage law. This could mean that workers could lose out on both the wage front as well as some important rights. This is particularly the case for farm workers who stand to lose important rights to housing.

How did it come to this?

You would have expected trade unions to have objected loudly to these fundamental changes to worker rights. Not so. The country’s leading trade union federations, including Cosatu, Fedusa and Nactu have all been involved in negotiations on the changes.

What this reflects is the balance of class forces in South Africa today. Trade union membership has been declining and now only about a quarter of the workforce is unionised. Of those that are unionised, the overwhelming majority are likely to be in full time, permanent, professional or skilled employment.

The simple truth is that unions largely do not organise workers who will benefit from the national minimum wage and are therefore indifferent to its practicalities.

Carin Runciman, Senior Reseacher, Centre for Social Change, University of Johannesburg

This article was originally published on The Conversation.