To understand South Africa today, we need to recognise that people can focus endlessly on a country’s problems but still live in a state of denial.

Hand-wringing about problems which are said to spell the doom of South Africa’s negotiated democracy is a well-established custom. It began only months after the first election in which all adults could vote in 1994. It has become louder over the past decade and dominates the national debate, which is the preserve of the minority who enjoy access to media.

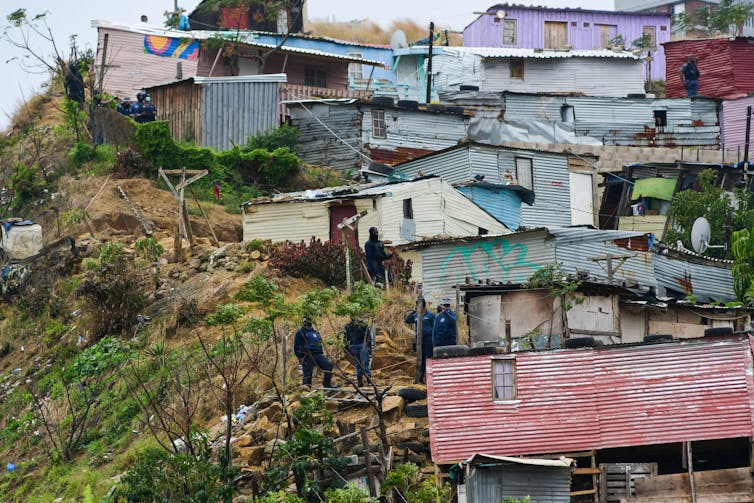

Right now, violence in the KwaZulu Natal province, attacks on the judiciary by former president Jacob Zuma and his supporters, and an unemployment rate of 34% are the immediate causes of dismay.

But, while the issues change, claims that the country is in deep trouble are routine.

Despite this, the national debate – which is restricted to an elite comprising around a third of the population – is in denial.

How can this be?

The debate’s diagnoses of doom denounce what works in post-1994 South Africa while ignoring or misrepresenting the stubborn and very real problems which prevent democracy from realising its potential. In particular, blaming the governing African National Congress (ANC) has become a substitute for facing deep-rooted problems which would remain whoever governed.

How the denial works

To illustrate how this type of denial works, the three problems which are currently in focus are all real – but far too real to be blamed only on some politicians.

The violence was a result of an incomplete journey to democracy, which means that the security forces are deeply factionalised and that corrupt networks will use violence to protect their turf.

Read more: Violence in South Africa: an uprising of elites, not of the people

Yet it is blamed purely on police incompetence or poverty. And the ANC is blamed for both.

The attacks on judges are treated with alarm despite the fact that they are no threat to the constitutional order. They have little credibility in the national debate because they are clearly ploys by politicians desperate to escape prosecution for corruption. Their credibility is further undermined by the fact that those who denounce the judges never hesitate to use the courts when this suits them.

But a real threat to the justice system which has been evident for years – in which grassroots citizens whose living areas are plagued by violence are impatient with due legal process and the courts – is hardly noticed in the now routine rush to blame ANC politicians.

The unemployment figures have prompted much denunciation of the government. But there was no similar reaction in 2003 when the rate was 31%. This went unnoticed because the economy was doing well for the minority able to benefit from it. Since they dominate the debate, it simply ignored reality.

Nor has anyone pointed out that unemployment has been growing for 50 years and that the lowest jobless numbers of the past two decades were higher than those in the Netherlands during the Great Depression.

The debate is in denial over the reality that unemployment is a deep-rooted and long-standing problem.

The denial does not necessarily target the governing party directly. So, a prominent theme is criticism of the political system despite the fact that it works largely as it meant to for the minority whose voices are heard.

Moves are afoot to change the electoral system “to ensure more accountable government”, despite the fact that local government already has the system to which the debate wants to move and is widely agreed to be a site of very little accountability.

A set of hearings at the commission of inquiry into Zuma-era corruption began a pattern in which parliament is said to be defective because it did not hold the ANC to account. The search is on for legal fixes which will force it to do what the one-third who take part in the debate want. Secret ballots are demanded for parliamentary votes in the hope that legislators will do what the debate wants, not what the parties for whom citizens voted want.

None of the proposed changes would make democracy work better – most would weaken it. Changing to an electoral system used by deeply unpopular municipalities will solve nothing; encouraging legislators to hide from voters when they cast ballots will strengthen elites and weaken the citizenry.

The whole point of parliaments is that they give the power to make decisions to the party which wins a majority. Rules to curb that will take the country back to minority rule, not forward to a brighter future. South African democracy works well for those who can make themselves heard – so well that, in a country where it was once common to fear that the ANC would control too much, it is routinely denounced by anyone who wants to be taken seriously by the debate.

Why this frenzy to fix what is not broken? Because the political system will not satisfy the debate as long it allows the ANC to govern. Supporters of a changed electoral system claim it would weaken “party bosses”. So do those who want to force parliament to do what they want and those who want legislators to be allowed to cheat on their voters.

In all three cases, “party bosses” is code for the leadership of the governing party.

Facing deep-rooted problems

The key point here is not that the ANC should not be held to account. Trying to ensure that the governing party does what citizens want it to do is a core feature of democracy. Voters being rude about the governing party is a democratic habit.

The ANC has much for which it should be forced to account: it did not create most of the patterns for which it is blamed, but has done far too little to change them and often seems happy simply to live with them.

But there is a huge difference between holding a governing party to account and making it an excuse for failing to face deep-rooted problems. Fixating on the ANC has given the one-third an excuse not to face difficult realities.

South Africa is a country beset by many problems, only one of which it solved in 1994 – the fact that 90% of the population were denied citizenship rights. Its problems routinely create crises which could be opportunities to face deep-rooted problems. But the opportunities are routinely wasted by a national debate which finds blaming a political party and its current leaders a convenient way of ducking responsibility for tackling these realities.

As long as that continues, the problems will persist because the prospect of tackling them will be drowned out by angry denial.![]()

Steven Friedman, Professor of Political Studies, University of Johannesburg

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.