There is no documented health benefit that warrants banning cigarette sales for 21 days.

Getty Images

What do South Africa, China, Germany, the UK and the US have in common? That each differs from the other. Ample empirical evidence shows that economic and health measures that work sometimes, in some places, don’t always work everywhere.

South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa has been praised for being decisive in the face of the COVID-19 outbreak. We agree with this positive view. Ramaphosa has demonstrated a quality of leadership matched by disappointingly few leaders globally. But we fear that some of the recently implemented policies are not best for the South African context. South Africa could be charting its own course, for the benefit of the nation and continent.

As matters stand, the South African lockdown emulates and, in some respects, surpasses restrictions elsewhere. Some of the restrictions are gratuitous, impractical or harmful.

What is lockdown in South Africa?

South African lockdown restrictions are among the most extreme globally. South Africans may not leave their homes except to procure essential goods and services. This excludes the purchase of cigarettes and alcohol. It also excludes outdoor exercise.

For those living in freestanding properties in the suburbs, and enjoying an uninterrupted salary from a large company or institution, the lockdown is a little like a spiritual retreat. They can stay at home and drink coffee in their pyjamas on the deck without even a passing car to disturb them.

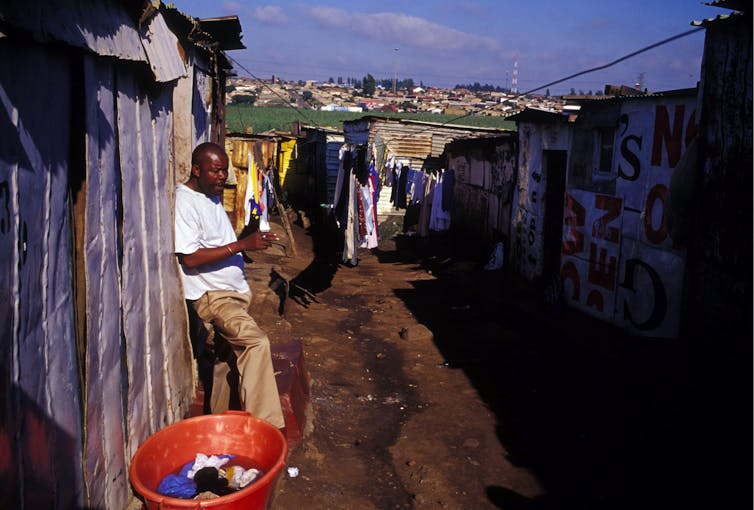

But most South Africans do not live like this. Even wealthy South Africans often live in complexes or estates without access to non-communal outside space. And many more live in crowded accommodation, whether in poor urban areas, formerly wealthy suburbs, central business districts, or well-spaced rural dwellings that are nonetheless occupied by many people.

It is one thing to stay in a suburban house, with a nice garden for fresh air and sunshine. It is another to spend the day in a small shack with 10 other people, especially when only “an estimated 46.3% of households had access to piped water in their dwellings in 2018”.

Domestic violence, rape and child abuse are serious problems in South Africa. Most of these crimes are committed by people close to the victim. The lockdown measures are likely to place stress on abusers and make it hard for the abused to escape.

It is no surprise that the lockdown restrictions are already being widely violated. This is not about disobedience: it is about the difficulty of complying. If you have to leave your dwelling merely to answer a call of nature, then you are not in a meaningful lockdown. And even with army support, policing will be extraordinarily difficult. Communities would need to fall into line of their own volition, and their circumstances make it hard for them to do so.

Cigarettes as essential goods

Nicotine withdrawal causes bad temper, frustration, agitation, anxiety and mood swings. The damaging health effects of smoking are well established, but although early stages of lung-recovery are visible a full month after one stops smoking, there is no evidence suggesting that COVID-19 symptoms are alleviated by 21 days of abstinence. There is no documented COVID-19 health benefit within a 21-day window to warrant prohibiting the sale of cigarettes. But there is considerable short-term risk to the mental wellbeing of those who use tobacco as a coping mechanism.

This restriction on civil liberties causes misery for no public health benefit and may increase the risk of domestic violence as people suffer withdrawal in confined and stressful circumstances.

The prohibition of alcohol makes more sense. But behavioural factors must be considered, including the incentive to stockpile and the criminal opportunity for bootlegging. Restricting alcohol purchase prior to the lockdown might have made sense. That window has closed. At this stage the case for putting alcohol on the list of essential goods is weak. The case for including cigarettes, however, is strong.

Outdoor exercise is essential

“No jogging. No dog walking. Stay inside.” That is the message from the government. This is a public health problem of note: exercise, even a small amount of it, is essential to stay healthy, especially for the elderly, and thus many of those most at risk from COVID-19.

Exercise, including mild exercise such as going for a walk, appears to alleviate or prevent depression. It is easy to write off the value of mental wellbeing at a time when serious physical disease threatens. But this is a mistake. Mental illness has physical consequences for the sufferer and those around them, and can make life seem not worth living.

When defining “essential goods and services”, we must ask “essential for what?” There is much that is not strictly essential to our survival that nonetheless we value greatly. We may even value some of these things above survival, such as the wellbeing of our children.

The current usage of the word “essential” imposes a value judgement. It makes the avoidance of COVID-19 infection the paramount goal. It implicitly places less value on mental health, and even physical health where that is independent of COVID-19.

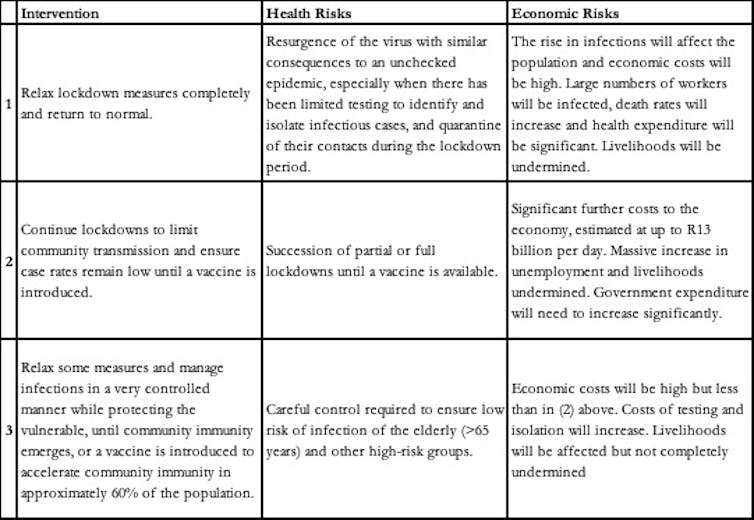

Is a lockdown right in South Africa?

Context matters. Whether the lockdown works depends on the context in which it is done. The lockdown is worthwhile if it prolongs life for a significant number of people. But some of the measures in South Africa have no health benefit.

South African leaders should consider the full range of responses available to them, and assess the costs and benefits within their context. Regional quarantine arguably failed in Italy, but was apparently more successful in China. South Africa was designed by the apartheid government to keep people apart.

What is to be done?

We are not advocating inaction or negligence. Reducing the rate of infection is a laudable goal. We would suggest, in particular, the addition of cigarettes to the list of basic goods, and the insertion of a right to exercise out of doors provided physical distance is maintained (along the lines of guidelines elsewhere).

More generally we suggest that, given very different conditions in relatively wealthy suburbs, inner cities, crowded low-income areas and rural areas, restrictions be considered on a provincial or local rather than a national basis. This is in line with the successful practice in China.

Benjamin T H Smart, Associate Professor, University of Johannesburg and Alex Broadbent, Director of the Institute for the Future of Knowledge and Professor of Philosophy, University of Johannesburg

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.