An elderly man at a social grant paypoint in South Africa after the COVID-19 lockdown. (Photo by MARCO LONGARI / AFP) ()

Photo by Marco Longari/AFP via Getty Images

The public debate on strategies to tackle COVID-19 often unhelpfully positions health and economic considerations in a diametric fashion – as trade-offs. In fact, economic policy has health consequences. And health policy has economic consequences. The two need to be seen as parts of a coherent whole.

In the case of South Africa, the country currently faces three interrelated problems. These are the public health threat from the COVID-19 pandemic, the economic and health effects of the lockdown, and a range of intractable economic problems not directly due to the current pandemic. These include high unemployment, low economic growth and falling per capita income.

Any potentially viable response to COVID-19 needs to address all three aspects in concert. This is particularly important as the country plans for the next stage of its response after the lockdown. Focusing only on the health challenges and not paying attention to the economic issues will result in significantly higher economic costs, and will also undermine the health imperatives.

Our view is that a protracted lockdown won’t necessarily have the effect of ridding the country of the virus, but it will result in unacceptably high health and economic consequences.

The cost

The initial lockdown was prudent and is likely to have lowered the risk of community spread of SARS-CoV-2.

But the true number of COVID-19 (the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2) cases is difficult to quantify. A limited number of tests have been done, and community-wide screening for suspected infectious cases has been delayed.

The available evidence on the COVID-19 pandemic suggests that any initial containment of the disease through a lockdown will be short-lived. Also, it’s likely to result in a rebound of cases in the absence of aggressive community-wide screening for SARS-CoV-2 infectious cases, isolation of the identified cases and quarantine of their close contacts for at least 14 days.

On top of this, South Africa may find itself permanently harmed by the simultaneous destruction of both the demand and supply sides of the economy under an extended generalised lockdown.

This will have other unintended long term health and economic consequences. For example, an extended lockdown could result in the undermining of other health services, such as the immunisation of children.

The economic effects of a lockdown, too, are severe.

Early forecasts suggest significant economic disruption from the current lockdown, which is costing the economy an estimated R13 billion per day. Preliminary projections by the South African Reserve Bank indicate that South Africa could lose 370,000 jobs in 2020. Projections by private banking analysts (based on the initial 21-day lockdown) suggest a GDP contraction of 7% during 2020, leading to a fiscal deficit of 12% of GDP (forecast at 6.8% in the 2020 budget) and a debt-to-GDP ratio in excess of 81% in 2021. This means that the country’s already limited public finances will be further constrained.

Towards a post-lockdown strategy

Globally, attention is turning from initial containment through generalised lockdowns to short- and medium-term risk-based public health and economic strategies. We present some considerations for a health and economic policy beyond the lockdown in South Africa.

In this we proceed from the following assumptions:

- The SARS-CoV-2 will not be eliminated in South Africa until either a vaccine is introduced (yet to be developed), or sufficient natural immunity in the population is achieved. It is therefore necessary to put in place and maintain a sustainable mitigation strategy for COVID-19 for the remainder of 2020, or until a vaccine is available (an optimistic timeline for this is 18-24 months).

- A generalised lockdown is not a viable long-term prevention strategy for COVID-19 due to its deleterious effects, including the resultant long-term impact on society, public health and the economy.

- Removal of the lockdown without appropriate health and economic measures will result in an excess mortality from COVID-19, resulting in further economic hardship.

South Africa’s health and economic strategy beyond the current lockdown must be designed to ensure good health care and be economically sustainable. We argue that the country needs to transition to a risk-based strategy which offers effective health protection and allows for the resumption of some economic activity.

This approach has been advocated by researchers in both Germany and the Indian state of Kerala.

Accordingly, the following objectives should be central to any policy.

- First, mitigate the rapid spread of the virus, while allowing for natural immunity in the population to increase gradually.

- Second, strengthen health care systems to ensure optimal treatment for as many patients as possible, both those with COVID-19 and those with other serious illnesses.

- Third, protect individuals at high risk for severe COVID-19 disease; and

- Fourth, make economic activities possible with measures in place to manage the health risks associated with these activities.

Economic and health strategies

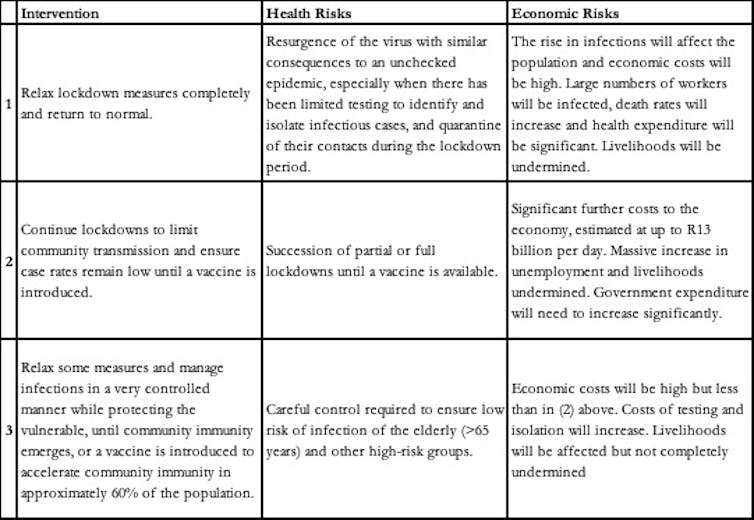

At the highest level, there are three broad intervention strategies available to South Africa (summarised in the table below), adapted from a recent article by leading Australian health academics James Trauer, Ben Marais and Emma McBryde. We believe that option three is the only practicable one for South Africa. And the details of its implementation matter.

Table 1: Typology of interventions and risks

Adapted from (Trauer et al., 2020)

A health strategy based on an extended generalised lockdown is economically unsustainable. It is also damaging to public health. Instead, we need a unified health and economic strategy that allows for some economic activity while inhibiting the uncontrolled spread of the virus. This requires a number of health and economic measures to be implemented in a coordinated manner.

First, to reduce the rate of infections, the country must have ready the capability of mass virus testing and efficient contact tracing before the end of April 2020. This must be accompanied by a comprehensive approach to social distancing. Relying solely on screening of symptomatic individuals will not effectively reduce the rate of infection because high viral loads of SARS-CoV-2 in the upper airway occur in pre-symptomatic and possibly asymptomatic people.

To be successful, the scale of testing needs to be at least equivalent to that in South Korea (17,322 tests per day in South Africa, eventually testing 1 in 150 people). At best, it must be equivalent to that carried out in Germany (36,399 tests per day in South Africa).

Test turnaround times must result in identification of infected individuals within 12 to a maximum of 24 hours. This must be followed by immediate isolation and contact tracing. Isolation of infected individuals and contact quarantine must last for at least 14 days, either at home, if suitable, or in designated isolation and quarantine facilities.

The annual cost of conducting 17,000 tests per day is approximately R5 billion. There would perhaps be an additional annual cost of R4 billion for contact tracing and quarantine. These costs compare favourably to the daily economic cost (R13 billion) of the generalised lockdown.

Secondly, economic activities must be allowed in a way that is consistent with the aim of preventing the uncontrolled spread of the virus. Within the constraints of the health strategy outlined above, a risk-based economic strategy is required that balances economic and health imperatives.

Decisions on differential opening of the economy should be made in line with the criteria proposed in a recent paper by German researchers. This includes, for example, opening sectors with low risk of infection (highly automated factories) and less vulnerable populations (child-care facilities) first. It could also include areas with lower infection rates and less potential for the spread of COVID-19. Of course, these decisions will have to be based on a careful assessment of factors such as household structure and composition in South Africa, and public transport.

To do this, the country will need excellent data on the extent and location of any community outbreaks of the virus. Such data will be generated by mass testing, and accurate information about the ability of certain sectors of the economy to reopen safely and in compliance with the health protocols.

The health and economic strategy will thus need to be implemented in a dynamic fashion, responding to the latest evidence.

This article has been amended to reflect updated estimates of the daily cost of the lockdown.

Cas Coovadia, member of the University of the Witwatersrand Council, also contributed to the discussions that led to the writing of this article

Shabir Madhi, Professor of Vaccinology and Director of the MRC Respiratory and Meningeal Pathogens Research Unit, University of the Witwatersrand; Alex van den Heever, Chair of Social Security Systems Administration and Management Studies, Adjunct Professor in the School of Governance, University of the Witwatersrand; David Francis, Deputy Director at the Southern Centre for Inequality Studies, University of the Witwatersrand; Imraan Valodia, Dean of the Faculty of Commerce, Law and Management, and Head of the Southern Centre for Inequality Studies, University of the Witwatersrand; Martin Veller, Dean of the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, and Michael Sachs, Adjunct Professor, Economics, University of the Witwatersrand

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.