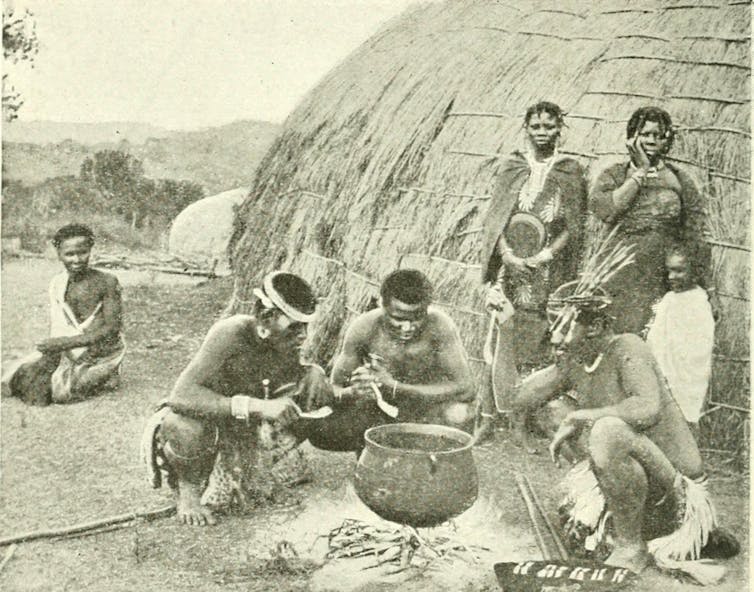

A Zulu household, from an 1895 book called The Colony of Natal: An Official Illustrated Handbook and Railway Guide.

J Causton and Sons /University of California Libraries/ Flickr

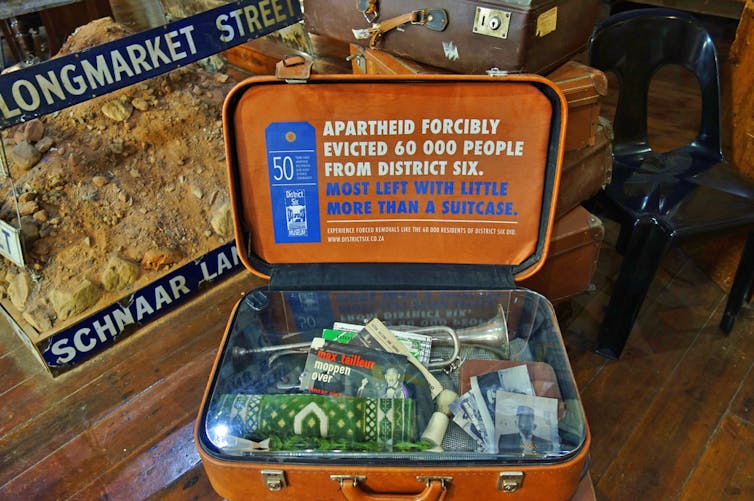

The post-apartheid state in South Africa inherited many colonial legacies. It has transformed considerably over the past 25 years. But it retains mechanisms of a state that secured power for a select few at the expense of most of its citizens.

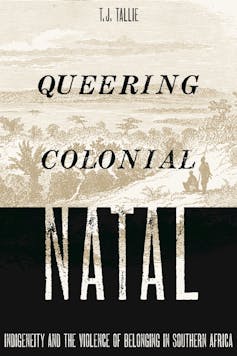

In my book, Queering Colonial Natal, I looked at the ways in which the settler state “queered” African and Indian social practices in the 19th century. By “queered” I mean that settler regimes defined these practices as threats to the social order they wanted to impose in colonial Natal —established by the British in 1843, today South Africa’s KwaZulu-Natal province. They did this by decrying the practices as inherently wrong and themselves as superior and civilised.

At the same time, colonial archives reveal that both African and Indian people (migrants who arrived in Natal from South Asia throughout the 19th century) challenged these claims. For example, parliamentary reports show that while settler marriage laws imposed monogamous, heterosexual unions as the only legitimate form of matrimony, local populations asserted the legitimacy of their own polygynous institutions in colonial courts.

I traced the complicated histories of race, sexuality and power in contemporary South Africa, focusing on colonial Natal. The colony offers a particularly valuable space to study as it hosted competing African, Indian and European settlers in relatively close proximity.

Understanding the social and legal issues in colonial Natal gives insight into the ways power operated in southern Africa – and the British Empire more broadly.

The entanglements of race, gender, class and sexuality in contemporary South Africa flow in part from the contradictions of the settler colonial state. In tracing the history, I believe it’s possible to see the long shadows that colonial history casts over the country’s complicated present. This provides the opportunity to see that situations aren’t inevitable. It is possible to look for new ways to understand and navigate the contradictions in our contemporary world.

Dissecting the colonial state

One of the major themes I looked at was state control. This extended to marriage and social reproduction, the legal managing of alcohol and the ways mission institutions claimed civilising power over all peoples. I also examined the politics of access to education in the colony. This was to show how different people used ideas of race and gender to claim legitimacy and belonging.

I argue that the colonial state attempted to mark African social practices as aberrant. Or, as I write in the book, as “queer”. This included practices such as isithembu (polygamy), ilobolo (the ceremonial offering of cattle from the groom’s family to the bride’s family), clothing and beer-drinking.

Settlers marked these practices as inherently wrong. They oriented themselves in opposition to them as a way of asserting their normalcy or civilised status.

Africans and Indians in Natal didn’t accept this labelling. As my research shows, they challenged it. Using occupation, belonging and settlement, people sought to challenge easy claims to power and authority. At the very least, they tried to “unsettle” them. They also used colonial courts to challenge legal pronouncements.

One case I examined was the continuous (and constantly challenged) effort of the settler state to ban alcohol consumption by Africans and Indians. The ban on Africans drinking liquor began in the 1850s. The Natal legislature debated – but frequently failed to pass – legislation banning the brewing or consumption of umqombothi, so-called “Native beer”, throughout this period.

Similarly, the access of Indian men and women to alcohol was restricted in 1890. They were allowed to consume beverages on site only and couldn’t take any liquor in bottles.

These restrictions mapped onto ideas in which settlers imagined Africans and Indians having diminished capacity for handling alcohol. But this led to a particular problem for white settlers when Europeans became intoxicated. The colonial record is filled with debates and anxious conversations about the problem of the supposedly rational and capable settler failing to handle his or her liquor, and the fear that this indicated a lack of social power and control.

The second chapter of my book discusses the ways in which African and Indian bodies were marked as inherently aberrant in order to create the figure of the fit, capable European drinker. Both of these fictions existed to uphold racial orders of power in the colony.

I also sought to unpack the ways in which historical framings of “queerness” led to reactionary homophobia as a means of defence.

Thinking through the messy, entangled histories of the past allows us to unsettle the difficulties of the present. Examining the power dynamics of the colonial state allows us to see how it still has an impact on contemporary society.

“Queering Colonial Natal: Indigeneity and the Violence of Belonging in Southern Africa” is available from University of Minnesota Press for $25.

T.J. Tallie, , University of San Diego

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.