Support for land redistribution tends to be stronger among economically disadvantaged South Africans.

EFE-EPA/Kim Ludrick

Unequal access to land in South Africa continues to prevent citizens from enjoying human dignity, rights and security. The ongoing debates and recent public hearings about land reform policy in the country are therefore crucial from a justice and development perspective. In deciding on the future direction of land policy, the views of citizens must be taken into account.

Land reform policy in South Africa has three core elements: restitution, redistribution and tenure reform. Restitution consists of claims for monetary compensation or the return of land that was forcibly taken away following June 1913. Land redistribution involves obtaining and transferring land to black farmers for various purposes. Lastly, tenure reform focuses on land rights for those whose rights are insecure due to past discrimination.

A review of the Human Sciences Research Council’s South African Social Attitudes Survey revealed certain trends in thinking about land reform over the years. The HSRC has been conducting this survey annually since 2003, tracking social, economic and political values among a representative sample of South Africans.

The survey analysis shows that over the past 15 years, most South Africans have supported the idea of land reform in principle. But the support isn’t commonly shared across social groups. And support for the policy isn’t matched by satisfaction with the government efforts in practice. This has implications for the degree to which land policy choices are likely to be contested, as well as for political pressure to respond to public expectations.

The participants were asked:

To what extent do you agree or disagree that government should redistribute land to black South Africans?

Answers were recorded using a 5-point agreement scale.

Robust support for land reform

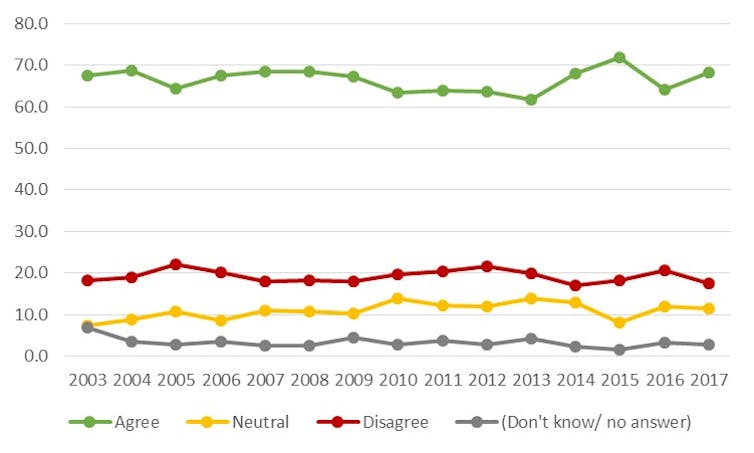

The graph in Figure 1 presents national trends based on the land reform question. It shows a generally consistent pattern in public preferences for land reform since the early 2000s. Over the period, an average of 67% of South African adults favoured land reform. The support ranged between a low of 62% and a high of 72%. In contrast, around a fifth of South Africans voiced opposition to land reform (19% on average, ranging from 17% to 22%), a tenth (11%) were neutral, and just 3% were uncertain.

Figure 1: Support for land reform in South Africa, 2003-2017 (%)

HSRC South African Social Attitudes Survey (SASAS) rounds 1-15, 2003-2017

A slight upswing in support has occurred since 2013. This possibly reflects the growing prominence of the issue in political discussion and a sense of urgency around addressing the land question.

How unified are South Africans?

While two-thirds of South Africans favour land reform in principle, support tends to follow lines of race, class and political party identification.

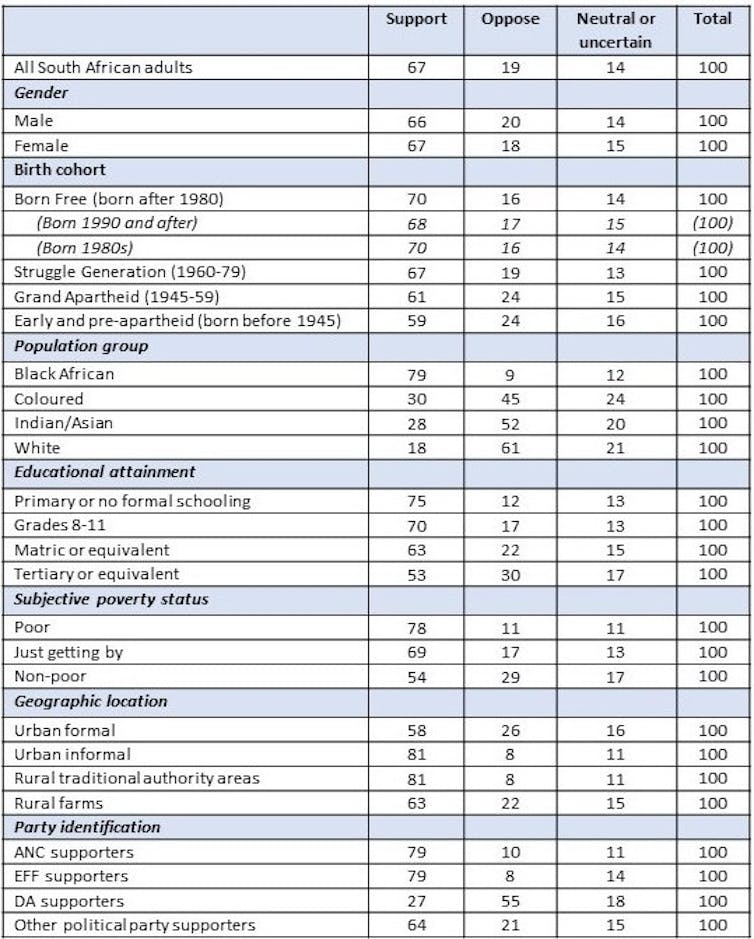

Table 1 presents all-year averages (combined data covering 2003-2017) based on gender, birth cohort, population group, educational attainment, subjective poverty status and type of geographic location.

Age doesn’t appear to have a very strong influence on people’s opinions, though younger people are slightly more inclined to support land reform than older adults. Neither is gender a significant factor.

Table 1: Support for land reform among South African adults on average between 2003 and 2017 (row %)

Note: The percentages in the table are based on combined data over the 2003-2017 period, meaning that the results should be interpreted as all-year averages.

HSRC South African Social Attitudes Survey rounds 1-15, 2003-2017

Race, as defined by South Africa’s previous system of classification, is a factor in the results: 79% of black African adults support land reform compared to slightly over a quarter of coloured and Indian adults and only 18% of white adults. To some degree this is informed by differences based on social class.

There is also a 20 to 25 percentage point difference in support based on educational status, subjective poverty status and geographic location. Support for the idea of land redistribution therefore tends to be stronger among economically disadvantaged South Africans. Politically, support for land reform is similar (79%) among supporters of the ruling African National Congress, which has been in power since 1994, and the Economic Freedom Fighters, a more left-wing party established in 2013. But the divide between these groups and supporters of the official opposition party, the Democratic Alliance, is more than 50 percentage points. This is likely to reflect a combination of individual preferences, societal position as well as party positions on land reform.

The survey findings show that there continues to be opposition to land redistribution among a significant minority. The fact that this opposition is more apparent among elites and the historically privileged means that policy proposals that challenge the status quo are likely to remain highly contested.

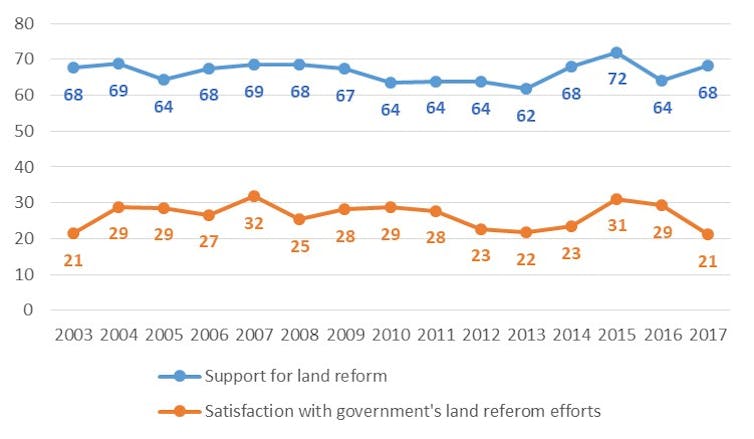

After nearly 25 years of post-apartheid land reform, a significant gap remains between support for land reform and evaluations of government performance in this area. South Africans rate progress in the implementation of land policy in a harsh light. This discontent with performance is more even shared across social groups.

When the last survey was undertaken in late 2017, only 21% of adults were satisfied with government’s progress in carrying out land reform. Satisfaction fluctuated between 21% and 32% over the 15 year history of the survey. Current levels of satisfaction are lower than ever before, which may partly explain why this policy issue has once again come under the spotlight. People are looking for new approaches that may get better results.

Figure 2: The gap between support for land reform and evaluations of state progress, 2003-2017 (%)

HSRC South African Social Attitudes Survey (SASAS) rounds 1-15, 2003-2017

The trends in the HSRC survey also point to the polarising nature and complexities associated with land debates.

Despite such evidence, a fuller, more nuanced examination of land reform attitudes and policy preferences and how they are changing over time is required. This should take into account current and envisaged policy considerations, such as expropriation, compensation and constitutional amendment.

Jare Struwig, Chief Research Manager, Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC), and Thobeka Radebe, a researcher in the HSRC’s Democracy, Governance and Service Delivery unit, contributed to the research.

Benjamin Roberts, Chief Research Specialist and Coordinator of the South African Social Attitudes Survey (SASAS), Human Sciences Research Council and Narnia Bohler-Muller, Executive Director of the Democracy, Governance and Service Delivery Programme at the Human Sciences Research Council and Adjunct Professor of Law, University of Fort Hare, University of Fort Hare

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.