|

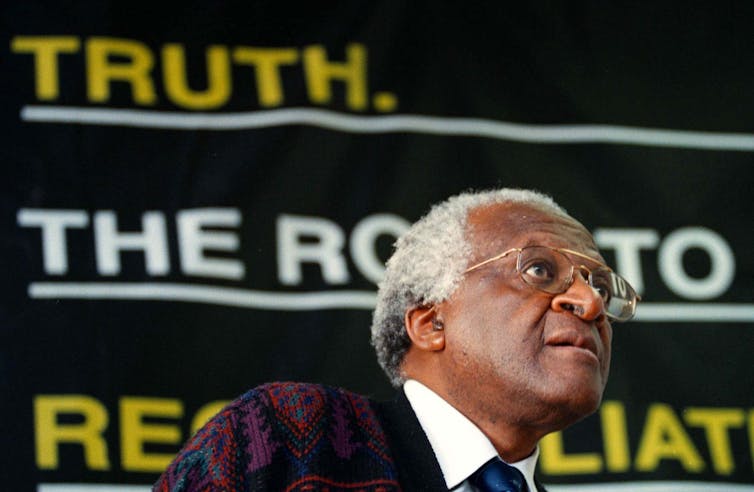

| Bishop Desmond Tutu during South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission process. Reuters |

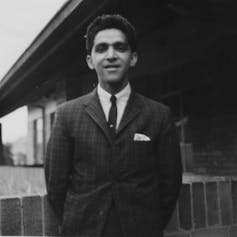

A powerful legal precedent that promises to see the reopening of other apartheid era crimes has been set in motion thanks to anti-apartheid activist Ahmed Timol’s family. They pushed for a new inquiry into Timol’s death, in 1971, while in police custody. An inquest held a year later found that he committed suicide while in detention. Now a judge has found that Timol was pushed to his death. The outcome refocuses the spotlight on how societies deal with authoritarian pasts.

In 1989 the Prime Minister of Poland, Tadeusz Mazowiecki, famously called for a “thick line” to separate the past and current political dispensations in Poland. The country was emerging from more than 40 years of communist rule that had been toppled by a popular uprising. Mazowiecki called for those who had been in power to be absolved of responsibility for their crimes to enable Poland to move forward.

South Africa, meanwhile, opted for a trade-off between culpability and truth after the fall of apartheid. Apartheid era offenders were required to give full disclosure of their crimes in exchange for amnesty. This was done under the auspices of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC).

The TRC built on the precedent of similar commissions set up in South American countries that had been through military rule. The TRC gave South Africa great international attention as it was viewed as a stellar success. As a result South Africa has been held up as a benchmark of how to deal with post conflict situations.

Ahmed Timol.

Ahmed Timol Family Trust

The model has been applied in different scenarios, ranging from Ireland’s sectarian conflict to Canada’s treatment of its First Peoples.

But more than 20 years after the formation of the TRC South Africans have become increasingly restive about its success. Critics say that rather than achieving truth and reconciliation, truth was sacrificed for reconciliation.

Dealing with the past

The transition in South Africa was informed by the 1980s series Transitions from Authoritarian Rule, edited by Guillermo O’Donnell, Philippe C. Schmitter and Laurence Whitehead, in the wake of authoritarian regimes collapsing in Latin America.

In comparing these transitions, they spelt out the steps societies would take in the future. Beginning with liberalisation, where general rights would be extended to all, they predicted that societies would then move to democratisation, where political rights would be democratised. The last step, socialisation, would provide social and economic equality.

As Wits University academic David Everatt has observed, this reasoning looks increasingly determinist. This is because it is obvious that South Africa and other post-authoritarian regimes have struggled to match the steps of liberalisation and democratisation with socialisation.

In effect, the steps set out in the Transitions series were also advocating for a “thick line” approach to dealing with the past. This underplayed the collective psychological trauma borne by those emerging from authoritarian societies, as was the case for black South Africans.

But the fundamental criminality of the apartheid system has provided ample grounds for families of victims to reopen inquests.

The desire of individual families, such as the Timols, to get to the truth of the death of their loved ones – and if possible, to see those responsible prosecuted – has ensured that further cases will be opened.

It has by no means been smooth sailing though: take the case of Neil Aggett, the trade unionist who died in police detention in 1982. A biography on Aggett written by Beverley Naidoo in 2012, Death of an Idealist, led to an article in a local newspaper exposing how one of Aggett’s main interrogators, Stephan Whitehead, had gone on to enjoy a successful career in the security forces after 1994.

The Neil Aggett Support Group – formed by his friends, family, lawyers and activists – wrote an open letter to Jeff Radebe, the then-Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development in February 2013. They called for the prosecution of Whitehead, who did not apply for amnesty to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. But the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) failed to take action.

Their experience mirrored that of Timol’s family who had faced obstacles at every step. Timol, a South African Communist Party member, died in very similar circumstances to Aggett’s at the same John Vorster Square in 1971.

Imtiaz Cajee, Ahmed Timol’s nephew, during the inquest into his death.

ANA/Jacques Naude

The Timol family saw an application they filed in 2003 turned down by the NPA. In 2016 the family presented new evidence that finally led the NPA to reopen the inquest later that year.

The Timol family have finally won what they fought so hard to achieve. The judge’s finding that Timol was pushed to his death has set a powerful legal precedent that promises to see other apartheid era crimes reopened.

Ian Macqueen, Lecturer, Department of Historical and Heritage Studies, University of Pretoria

This article was originally published on The Conversation.