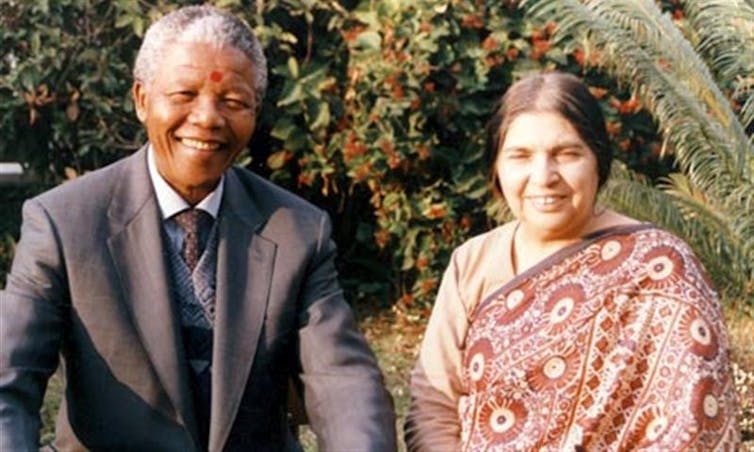

Nelson Mandela and his comrade, anti-apartheid activist, Fatima Meer.

Indian Spice

South Africa’s apartheid social engineering, the post-1994 victory over racialised inequality and the subsequent recognition that the victory may have been Pyrrhic have elicited a vast literary response, including a fascinating body of personal responses in the form of memoirs, biographies and autobiographies.

These narratives have sought to memorialise significant lives that drove the anti-apartheid struggle, and often focused on documenting the times that created the people.

An emerging trend is one that foregrounds the family in the lives of activists, rather than the established paradigm of the autonomous national auto/biographical hero. Examples that signal this shift are Gillian Slovo’s “Every Secret Thing” (1997) and Elinor Sisulu’s “Walter and Albertina Sisulu: In Our Lifetime” (2002).

These auto/biographies take the social microcosm of the family, both nuclear and extended, as the most important matrix out of which lives committed to social justice emerge. They are then placed within the broader context of the nation.

Eros at the heart

“Love in the Time of Treason: The Life Story of Ayesha Dawood” (2008) by Zubeida Jaffer and the autobiography, “Fatima Meer: Memories of Love and Struggle” (2017), acknowledge and recollect the households that created – and are created by – political activists – households which occupy a shifting space between private and public spheres. What sets these two life narratives in relief is the way in which they position eros at the heart of the narrative.

Cover of ‘The Life Story of Ayesha Dawood’.

Veteran journalist, Zubeida Jaffer, presents a portrait of an extraordinary person in decidedly ordinary, yet moving terms. Ayesha Dawood was a young woman in the little country town of Worcester near Cape Town in the 1950s when the first effects of apartheid were being felt. Despite a conservative, sheltered upbringing as the daughter of an Indian shopkeeper, Ayesha is drawn into various social protests and the trade union movement through her innate sense of justice.

Ayesha’s political involvement leads to her being arrested and tried at the Treason Trial of 1956 along with Nelson Mandela, and various other more high profile figures. She also subsequently is jailed and kept in solitary confinement for an extended period in a women’s prison in the nearby town of Paarl.

But contrary to expectation, the biography is not constructed around her activist experience. In fact, the biography does not even open with a focus on Ayesha. Instead, the story of her South African struggle experience begins with her future husband in India.

The narrative is constructed as a love story. It’s a love obstructed by numerous separations. Yusuf Mukadam falls in love with Ayesha at first sight in the village in India where she visits her grandmother. After her departure, despite no real contact with or commitment from her, Yusuf later joins the merchant navy as a cook. His sole purpose: to meet Ayesha again in Cape Town as part of a two-year voyage.

Yusuf sends a letter to inform her of his arrival. But the letter is never opened since Ayesha is in police custody at the time. Yusuf arrives in Cape Town and thinks he has been spurned when he is not met as arranged.

Some years later, back in India, he discovers why he didn’t get a response from the woman to whom he feels incontrovertibly and inexplicably bound. He then signs up for another voyage. This time he jumps ship in Durban and travels to Cape Town to meet and marry Ayesha, almost a decade after their first meeting.

Years into their marriage, after the birth of two children, Yusuf is arrested as an illegal immigrant. But the arrest is a pretext to blackmail Ayesha into acting as a police informant. Since she does not cooperate, her husband is deported to India, an exile which she shares with her life partner.

The poverty of the Indian village means that Yusuf must become a migrant worker in Kuwait in order to support Ayesha and the children. The family finally returns to South Africa, many years later, after the release of Mandela.

Throughout the biography, Jaffer foregrounds romantic attachments. The narrative is prologued by the occasion when Ayesha sees Mandela again on his visit to Worcester on the Blue Train in 1997. The bonds of intimacy between Mandela and Graça Machel at the train station, and Ayesha and Yusuf, are paralleled.

The biography is structured around and locates its narrative momentum in this enduring, ethically cognisant love – or as Jaffer has Ayesha succinctly utter:

Yusuf is my taqdeer (destiny).

Complex relationship

The love relationship is similarly foregrounded in internationally recognised academic-activist Fatima Meer’s autobiography, posthumously published by her daughter.

Cover of ‘Fatima Meer: Memories of Love and Struggle’.

What is surprising about Meer’s autobiography is the way in which the complex relationship with her husband, prominent struggle lawyer Ismail Meer, is used as the organising principle around which her life story is told.

If Yusuf was Ayesha’s destiny, Ismail seems to shape the destiny of Fatima. The Meer relationship is a curious one where a member of the extended family whom she had regarded as an uncle later comes to be her husband when they proverbially fall head-over-heels in love. As trusted “uncle”, Ismail plays a role in determining that Fatima, constrained by a conservative community, should get to study away from home at the University of the Witwatersrand, and influences what she should study.

In a somewhat less tranquil relationship than that of Ayesha and Yusuf, Fatima presents her husband, despite his fierce temper and tendency to domineer, as the central pole and pulse of her life. Fatima’s is a life that is internationally known for never being cowed, a life remembered for its outspoken, principled defiance and critique, even of comrades.

F. Fiona Moolla, Senior Lecturer in English, University of the Western Cape

This article was originally published on The Conversation.