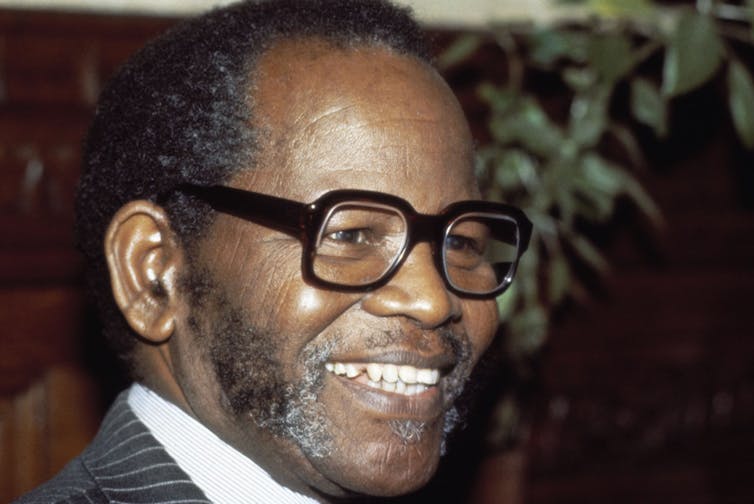

Running out of options. Finance Minister Malusi Gigaba speaks after delivering his medium term budget.

REUTERS/Sumaya Hisham

South Africa’s 2017 medium-term budget policy statement represents a watershed moment in the post-apartheid economic and fiscal position. The best thing that can be said about it, is that it was at least frankly honest about the situation the country is facing. Arguably, there was no choice. The country has reached a situation where it’s no longer possible to spin the notion that public debt is under control.

In recent years, South Africa’s National Treasury has desperately, and creatively, tried to avoid making deep cuts to government expenditure, or imposing drastic revenue raising measures on citizens. It did this while still convincing investors and credit ratings agencies that public finances would stabilise.

But the 2017 medium term budget makes it clear that the project has essentially reached the end of the road. The notion that national debt will stabilise has now effectively had to be abandoned. South Africa’s latest finance minister, Malusi Gigaba, effectively gave up on the debt targets set out by Pravin Gordhan a year ago when he stated that net national debt as a percent of GDP should stabilise at 47.9% by 2019/20. Gigaba announced yesterday that this is expected to be 49.1% by the end of this fiscal year, increasing to 53.9% by 2019/20.

This is a clear sign that any attempt to stabilise debt has failed. A further ratings downgrade is now highly likely. And it will be worse than the last one which only affected foreign currency debt. Gigaba’s budget proposals are likely to lead to a downgrade of the country’s local denominated debt, which will increase government borrowing costs and could lead to significant capital outflows. Even without a downgrade the medium term budget reveals that debt service costs are expected to increase from 11% of total expenditure to 15% over the next few years.

Without higher revenue, that means less money to spend on government’s constitutional obligations and policy commitments. Unfortunately, the gloomy story is largely driven by a massive shortfall in revenue collection of R50.8 billion. So attempting to avoid these consequences through taxation is not looking like a feasible option.

In the current political environment, even the best case scenario is grim. In fact the country’s finances could worsen even further if the outcome of the governing party’s elective conference in December doesn’t see a return to good governance and responsible fiscal management.

Slippery slope since 2008

In the years since the global financial crisis that started in 2008, the government allowed expenditure to increase faster than growth and revenue. This was done with the hope of offsetting the short-term effects of the crisis and getting the country back onto a stable path of significant economic growth.

That led to a rapid increase in national debt relative to the size of the economy. But the failure of the economy to recover – due in part to political instability, bad decision making and poor governance – meant that this approach became unsustainable.

In the last few years successive national budgets have walked a tightrope in trying to contain the growth in debt. Planned spending has been reduced, while some tax rates have been increased and new tax instruments introduced. Amid all these manoeuvres, dramatic cuts to government expenditure, or wide-reaching increases in taxes, have been avoided.

Efforts to arrest fiscal decline were sabotaged by the removal of Gordhan in March this year. His removal meant that the institutional reputation of the finance ministry was compromised and, since it was this that had kept the country’s credit ratings intact despite increasing fiscal pressure, the country’s foreign denominated debt was downgraded to “junk” (sub-investment grade).

Storm clouds on the horizon

As if the picture wasn’t gloomy enough, numerous risks to the fiscal projections and proposals loom on the horizon. South Africa’s president Jacob Zuma continues to sit on the higher education funding report, causing further instability at universities. That leaves open the possibility that more money for university students may be needed at short notice.

And the finances of various state owned enterprises are teetering, requiring increasing government support to prop them up. Since Gigaba took over the ministry he has taken R5.2 billion from the R6 billion “contingency reserve” – which is meant to be used for emergencies, or other unforeseeable events, such as natural disasters – to prop-up South African Airways. This broke with commitments to fund bailouts using revenue from asset sales. The medium term budget cements this breach – funds used to prop up the airline will not be replaced with funds from asset sales.

But the most menacing risk is the power utility Eskom, which is propped up by R350 billion in debt guarantees, but faces rising infrastructure costs, stagnant electricity demand and successive corruption scandals linked to state capture. Due to the scale of the commitments to Eskom, it will be impossible to contain the negative consequences if its lenders start refusing to rollover its debt.

No political will

Reading between the lines of the medium term budget, there is evidently no political will at the highest levels – the president and his cabinet – to do the right thing. The only reduction in planned expenditure is a cut to the contingency reserve. But responding to rising debt by reducing money for future emergencies is emblematic of the reluctance to take braver decisions like cutting the bloated, pointless ministries seemingly introduced by Zuma to employ his political cronies and their associates.

Seán Mfundza Muller, Senior Lecturer in Economics, University of Johannesburg

This article was originally published on The Conversation.