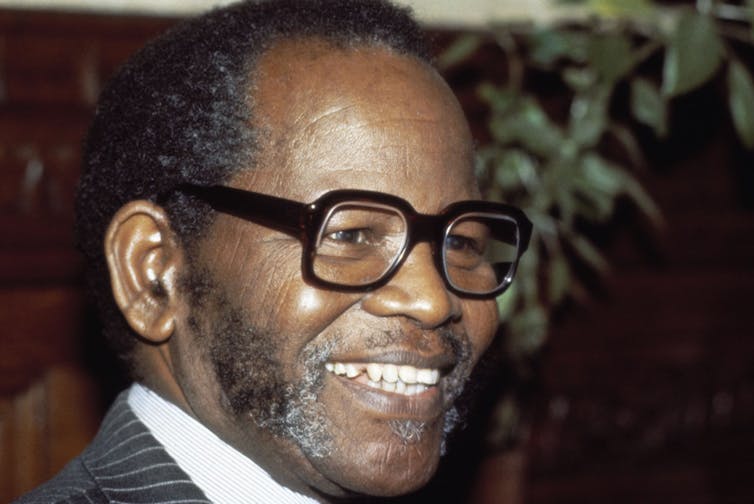

Oliver Reginald Tambo served as ANC president from 1967 to 1991.

Reuters

Oliver Tambo’s name and reputation are lauded, not least because he succeeded, remarkably, in keeping the African National Congress (ANC) together as a liberation movement during an exile lasting 30 years. Despite this legacy, the ANC, now South Africa’s governing party, has seen a year culminating in what is, arguably, its greatest crisis. Today, factions within the ANC nostalgically point to the example of Oliver Reginald Tambo , or OR as he was affectionately known in party circles.

Evidence of systemic corruption and factionalism for personal gain within the ANC are blamed for the failure to deliver improved living conditions to the poorest communities. The loss of three major metropolitan municipal councils in the industrial heartland testifies to diminished confidence in the ANC.

By contrast, in the year of his centenary, Oliver Tambo is held as an exemplar of integrity, personifying the ideal of a leader who for 50 years selflessly served the movement, consistently holding up the goals of a humane and caring society.

But who was this much talked about Tambo? And what lessons can be learnt from his leadership?

Exile

In 1960, after the Sharpeville massacre, then ANC President Chief Luthuli instructed Tambo to leave South Africa as an international diplomat of the ANC. His task was to mobilise a worldwide economic boycott.

With hindsight it was a prescient judgement call. The military wing of the ANC Umkhonto we Sizwe was launched a year later and within two years leaders of the ANC were facing charges of treason in the Rivonia Trial. The trial, which stretched through 1963-1964, led to life sentences for the leaders of Umkhonto we Sizwe, which included Walter Sisulu, Nelson Mandela, Govan Mbeki and Ahmed Kathrada.

Tambo’s task was to alert the world to the horrors of apartheid South Africa, and to seek assistance and support from newly independent states in Africa. It was to be more than 30 years before he returned home in December 1990. During this time, his integrity combined with his keen intellect and natural warmth impressed many people in diverse countries around the world.

Consensus seeker

Tambo was a careful and astute listener. He followed the indigenous African consensus system of decision making, crafting a conclusion that included at least some of the opinions of all participants.

He believed that the ANC should maintain the “high moral ground” and that it should be a broad umbrella under which all enemies of apartheid could shelter and enrich the movement, irrespective of their political beliefs. He was also cautious, likening the challenge of the liberation struggle to the traditional “indima” method of ploughing a very large piece of land. He explained at a Sophiatown meeting in 1953.

There’s a point where you must start. You can’t plough it all at once – you have to tackle it acre by acre…

One of Tambo’s strengths was his constructive and creative response to criticism. In 1967, for example, following the failure of Umkhonto we Sizwe cadres to reach the borders of South Africa after a battle at Wankie in “Rhodesia” (now Zimbabwe), Chris Hani and others, disillusioned with the leaders’ lethargy, released an angry memorandum. In an interview I did with Hani in Johannesburg in 1993 he admitted: “We blew our tops.” They accused the leadership of Umkhonto we Sizwe and the ANC of getting too comfortable and losing their appetite to return home – they had become “men in suits, clutching passports”.

The response by the leadership was outrage – the Secretary-General Alfred Nzo called for Hani’s execution for treason. But Tambo immediately began organising a conference of elected representatives of the branches around the world. A message was sent to Robben Island to inform ANC leaders jailed there, including Nelson Mandela, of this development.

It was time for frank conversation and a comprehensive, considered assessment. The outcome was the historic and constructive conference at Morogoro in Tanzania. The conference took on a more inclusive and democratic direction for the ANC, foregrounding the political aims over the military, and identifying the importance of mobilising workers at home.

Challenging 1980s

In the 1980s Tambo was faced with a more serious challenge. International attention against apartheid was growing; he was travelling extensively, persuading ordinary people to undermine apartheid by boycotting its products and banks and denying it arms. Alarmed, the apartheid regime sent spies into ANC camps on the continent, infiltrating top committees in Lusaka and other ANC structures.

The panic that ensued turned the spotlight on the flaws of the Umkhonto we Sizwe leadership. Human rights abuses of suspected spies and “ill-disciplined cadres” led to unlawful deaths and executions.

Tambo’s cautious response was criticised by the leadership of both ANC intelligence and Umkhonto we Sizwe for “impeding investigation” into the spies, owing to “his sense of democracy”. The chief culprits of these human rights abuses were formerly trusted peers of Tambo. He faced the dilemma of blowing the ANC wide apart if he challenged them. Instead, he resorted to the compromising strategy of redeploying them to other sections of the movement, such as education – perhaps leaving an unfortunate legacy for today’s ANC.

Enduring legacy

Tambo was to set in motion a process that culminated in South Africa’s democratic constitution. He:

- subscribed Umkhonto we Sizwe and the ANC to the Geneva Convention, which imposed a strict adherence to human rights.

- set up a commission of trusted senior comrades to look into the conditions in the ANC’s camps in Africa as well as abuses. The commission’s report was highly critical.

- summoned an consultative conference in Kabwe in 1985 that reaffirmed ANC’s humanist values, addressed gender inequalities and formally accepted whites in official positions.

- appointed the movement’s top legal minds to research and craft a constitution for the ANC; it was inspired by the Freedom Charter, which had been drawn up in 1956 after extensive consultation with ordinary people. It opened with the ringing words:

South Africa belongs to all who live in it.

South Africa’s new democracy essentially incorporated many of the clauses in the charter’s the path-breaking 1996 constitution.

Tambo’s insights remain relevant

Reporting to his first conference inside South Africa in December 1990 after the unbanning of the ANC, Tambo warned that “suspicions will not disappear overnight, the building of the South African nation is a national ask of paramount importance.

And he warned:

The struggle is far from over: if anything, it has become more complex and therefore more difficult.

He also reflected that "we were always ready to accept our mistakes and correct them.”

Faced by crises in the ANC, Tambo had always been ready to listen, responding constructively and creatively with new policies to meet the challenges of the time.

This is the enduring legacy of Oliver Tambo: many seasons later, many continue to gain insights and learn relevant lessons from his responses to the universal, human condition of our time. But whether they heeded this call is a moot point:

I have devotedly watched over the organisation all these years. I now hand it back to you, bigger, stronger - intact. Guard our precious movement.

Luli Callinicos, Researcher and founder member of the History Workshop, University of the Witwatersrand

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

No comments:

Post a Comment