Google and Apple have removed hundreds of apps from their app stores at the request of governments around the world, creating regional disparities in access to mobile apps at a time when many economies are becoming increasingly dependent on them.

The mobile phone giants have removed over 200 Chinese apps, including widely downloaded apps like TikTok, at the Indian government’s request in recent years. Similarly, the companies removed LinkedIn, an essential app for professional networking, from Russian app stores at the Russian government’s request.

However, access to apps is just one concern. Developers also regionalize apps, meaning they produce different versions for different countries. This raises the question of whether these apps differ in their security and privacy capabilities based on region.

In a perfect world, access to apps and app security and privacy capabilities would be consistent everywhere. Popular mobile apps should be available without increasing the risk that users are spied on or tracked based on what country they’re in, especially given that not every country has strong data protection regulations.

My colleagues and I recently studied the availability and privacy policies of thousands of globally popular apps on Google Play, the app store for Android devices, in 26 countries. We found differences in app availability, security and privacy.

While our study corroborates reports of takedowns due to government requests, we also found many differences introduced by app developers. We found instances of apps with settings and disclosures that expose users to higher or lower security and privacy risks depending on the country in which they’re downloaded.

Geoblocked apps

The countries and one special administrative region in our study are diverse in location, population and gross domestic product. They include the U.S., Germany, Hungary, Ukraine, Russia, South Korea, Turkey, Hong Kong and India. We also included countries like Iran, Zimbabwe and Tunisia, where it was difficult to collect data. We studied 5,684 globally popular apps, each with over 1 million installs, from the top 22 app categories, including Books and Reference, Education, Medical, and News and Magazines.

Our study showed high amounts of geoblocking, with 3,672 of 5,684 globally popular apps blocked in at least one of our 26 countries. Blocking by developers was significantly higher than takedowns requested by governments in all our countries and app categories. We found that Iran and Tunisia have the highest blocking rates, with apps like Microsoft Office, Adobe Reader, Flipboard and Google Books all unavailable for download.

We found regional overlap in the apps that are geoblocked. In European countries in our study – Germany, Hungary, Ireland and the U.K. – 479 of the same apps were geoblocked. Eight of those, including Blued and USA Today News, were blocked only in the European Union, possibly because of the region’s General Data Protection Regulation. Turkey, Ukraine and Russia also show similar blocking patterns, with high blocking of virtual private network apps in Turkey and Russia, which is consistent with the recent upsurge of surveillance laws.

Of the 61 country-specific takedowns by Google, 36 were unique to South Korea, including 17 gambling and gaming apps taken down in accordance with the national prohibition on online gambling. While the Indian government’s takedown of Chinese apps happened with full public disclosure, surprisingly most of the takedowns we observed occurred without much public awareness or debate.

Differences in security and privacy

The apps we downloaded from Google Play also showed differences based on country in their security and privacy capabilities. One hundred twenty-seven apps varied in what the apps were allowed to access on users’ mobile phones, 49 of which had additional permissions deemed “dangerous” by Google. Apps in Bahrain, Tunisia and Canada requested the most additional dangerous permissions.

Three VPN apps enable clear text communication in some countries, which allows unauthorized access to users’ communications. One hundred and eighteen apps varied in the number of ad trackers included in an app in some countries, with the categories Games, Entertainment and Social, with Iran and Ukraine having the most increases in the number of ad trackers compared to the baseline number common to all countries.

One hundred and three apps have differences based on country in their privacy policies. Users in countries not covered by data protection regulations, such as GDPR in the EU and the California Consumer Privacy Act in the U.S., are at higher privacy risk. For instance, 71 apps available from Google Play have clauses to comply with GDPR only in the EU and CCPA only in the U.S. Twenty-eight apps that use dangerous permissions make no mention of it, despite Google’s policy requiring them to do so.

The role of app stores

App stores allow developers to target their apps to users based on a wide array of factors, including their country and their device’s specific features. Though Google has taken some steps toward transparency in its app store, our research shows that there are shortcomings in Google’s auditing of the app ecosystem, some of which could put users’ security and privacy at risk.

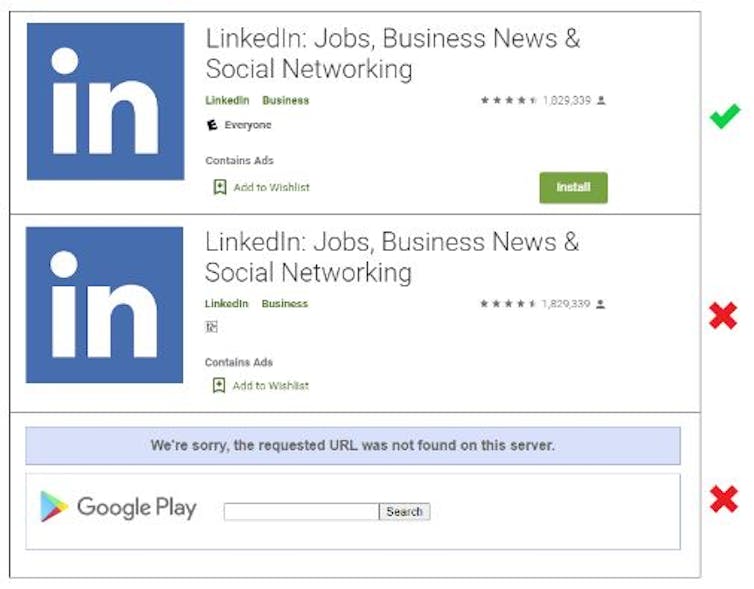

Potentially also as a result of app store policies in some countries, app stores that specialize in specific regions of the world are becoming increasingly popular. However, these app stores may not have adequate vetting policies, thereby allowing altered versions of apps to reach users. For example, a national government could pressure a developer to provide a version of an app that includes backdoor access. There is no straightforward way for users to distinguish an altered app from an unaltered one.

Our research provides several recommendations to app store proprietors to address the issues we found:

- Better moderate their country targeting features

- Provide detailed transparency reports on app takedowns

- Vet apps for differences based on country or region

- Push for transparency from developers on their need for the differences

- Host app privacy policies themselves to ensure their availability when the policies are blocked in certain countries

![]()

Renuka Kumar, Ph.D. student in Computer Science and Engineering, University of Michigan

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.