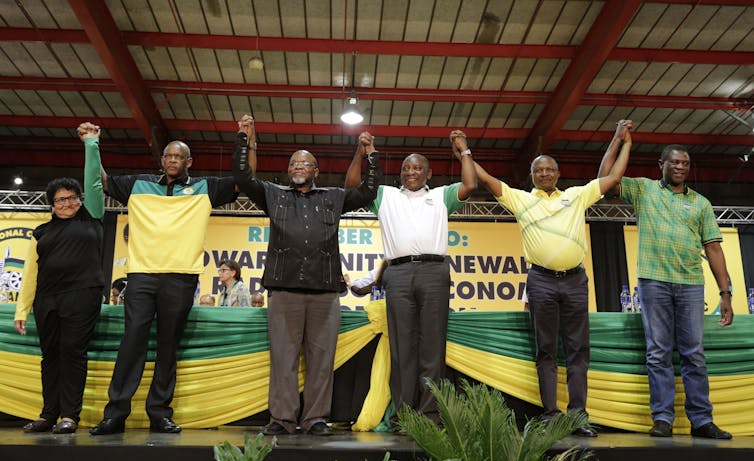

New ANC President Cyril Ramaphosa moments before winning.

EPA-EFE/Cornell Tukiri

South Africa’s governing party, the African National Congress (ANC), has a new president – Cyril Ramaphosa. But who is he?

Ramaphosa cuts a fitting figure to take over government, stabilise the economy, and secure the constitutional architecture that he helped create at the end of apartheid.

But to expect more would be expecting too much. He is unlikely to veer far from the traditional economic path chosen by the ANC.

There are some important features we can draw on to make some conjectures about the man.

The early days

Ramaphosa was born in Johannesburg, the industrial heartland of South Africa, on November 17, 1952. The second of three children, his father was a policeman. He grew up in Soweto where he attended primary and high school. He later went to Mphaphuli High School in Sibasa, Limpopo, were he was elected head of the Student Christian Movement soon after his arrival, attesting to his Christian beliefs.

He studied law at the then University of the North (Turfloop), where he became active in the South African Students Organisation, which was aligned to black consciousness ideology espoused by Steve Biko. He became active in the University Student Christian Movement, which was steeped in the liberation black theology of the black consciousness movement.

After graduating with a degree in law, Ramaphosa continued his political activism through the Black People’s Convention, for which he was jailed for six months. He went on to serve articles and joined the Council of Trade Unions of South Africa which was to form the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) with Ramaphosa as its first secretary general. He helped built the NUM into the largest trade union in the country, serving as its secretary general for just over 10 years.

Business and politics

His prominence and public stature grew even more when he was elected secretary general of the ANC in 1991. He went on to play a key role during South Africa’s transition, becoming one of the key architects of the country’s constitutional democracy.

Under the auspices of the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (Codesa), he became the ANC’s lead negotiator during negotiations on a post-apartheid arrangement.

Following this, he led the ANC team in drawing up a new constitution for the country. It is now considered one of the most progressive constitutions in the world.

In 1994 Ramaphosa lost the contest to become President Nelson Mandela’s deputy. Having Thabo Mbeki appointed instead was a blow, but persuaded by Mandela, Ramaphosa went into business.

For the next two decades Ramaphosa put his energies into building a large investment holding company Shanduka with interests in sectors ranging from mining to fast foods. The success of the group confirmed his reputation as a skilled dealmaker and negotiator.

During this 20-year period in business, Ramaphosa established deep links in the private sector in South Africa.

This set him at odds with sections of the ANC which believe that the post-apartheid arrangements delivered political power, but not economic freedom. These voices have become louder under President Jacob Zuma’s presidency with calls for radical economic transformation and action to tackle white monopoly capital.

Ramaphosa will have his work cut out for him as he tries to accommodate these demands by driving a more inclusive social compact in the country while simultaneously trying to manage rampant corruption in the private and public sectors.

Road to presidency

Even during his years in business Ramaphosa remained close to the ANC, serving as a member of the national disciplinary committee.

But he made his major comeback onto the political scene at the ANC’s 2012 elective conference in Mangaung, Bloemfontein where he was elected deputy president of the ANC, and later of the country.

Two years prior to this Ramaphosa became deputy chairman of the state-run National Planning Commission. He presided over its diagnostic report, which set out the problems facing the country in clear terms. A plan was drawn up to provide answers to the challenges identified in report. Known as the National Development Plan, it was tabled as a blue print for the type of society South Africa could become.

The plan showed Ramaphosa’s strengths as an architect of social compacts.

Since its tabling the plan has been left to gather dust. But it remains a point of reference, and serves as a counterpoint to calls for radical economic transformation.

Ramaphosa is likely to emphasise stability – in government and the ANC. Given his history he is likely to want to stabilise the economy rather than to pursue radical interventions.

Ramaphosa has a personal interest to secure a stabilising social compact akin to the one he negotiated in 1994 given developments that have left the country economically and socially weaker. These have included allegations that parts of the state have been taken over by corrupt civil servants and some private sector interests, high levels of unemployment and increasingly fractious public debates.

Not surprisingly during his campaign trail he moulded his image on the sanctity of the rule of law and on the dictum that social stability hinges on respect of the rule of law.

The big question mark over Ramaphosa is how effective he will be. Although he’s been the deputy president of the ANC and of the country for five years, some believe that his influence has been minimal and that he has not been able to imprint his leadership on the party – or the country.

Thapelo Tselapedi, Politics lecturer, Rhodes University

This article was originally published on The Conversation.