The SARS-CoV-2 virus mutates fast. That’s a concern because these more transmissible variants of SARS-CoV-2 are now present in the U.S., U.K. and South Africa and other countries, and many people are wondering whether the current vaccines will protect the recipients from the virus. Furthermore, many question whether we will we be able to keep ahead of future variants of SARS-CoV-2, which will certainly arise.

In my laboratory I study the molecular structure of RNA viruses – like the one that causes COVID-19 – and how they replicate and multiply in the host. As the virus infects more people and the pandemic spreads, SARS-CoV-2 continues to evolve. This process of evolution is constant and it allows the virus to sample its environment and select changes that make it grow more efficiently. Thus, it is important to monitor viruses for such new mutations that could make them more deadly, more transmissible or both.

RNA viruses evolve quickly

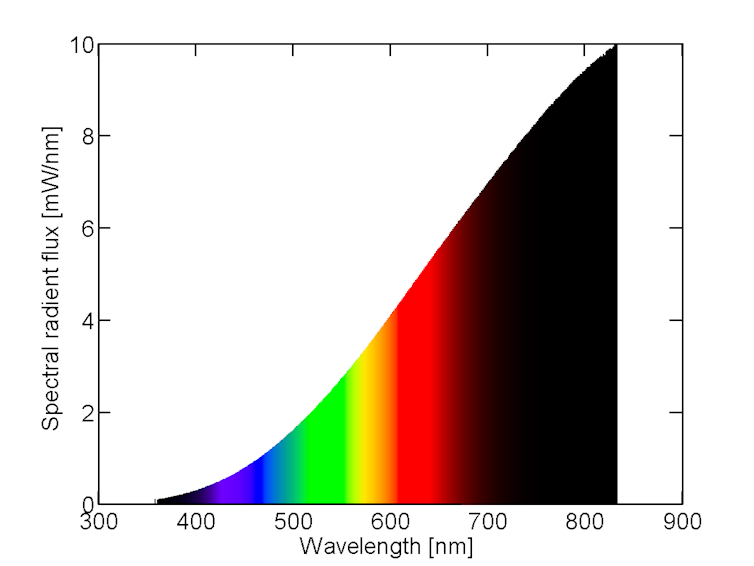

The genetic material of all viruses is encoded in either DNA or RNA; one interesting feature of RNA viruses is that they change much more rapidly than DNA viruses. Every time they make a copy of their genes they make one or a few mistakes. This is expected to occur many times within the body of an individual who is infected with COVID-19.

One might think that making a mistake in your genetic information is bad – after all, that’s the basis for genetic diseases in humans. For an RNA virus, a single change in its genome may render it “dead.” That’s not too bad if inside an infected human cell you’re making thousands of copies and a few are no longer useful.

However, some genomes may pick up a change that is beneficial for the survival of the virus: Maybe the change allows the virus to evade an antibody – a protein that the immune system produces to catch viruses – or an antiviral drug. Another beneficial change may allow the virus to infect a different type of cell or even a different species of animal. This is likely the pathway that allowed SARS-CoV-2 to move from bats into humans.

Any change that gives the virus’s descendants a competitive growth advantage will be favored – “selected” – and begin to outgrow the original parent virus. SARS-CoV-2 is demonstrating this feature now with new variants arising that have enhanced growth properties. Understanding the nature of these changes in the genome will provide scientists with guidance to develop countermeasures. This is the classic cat-and-mouse scenario.

In an infected patient there are hundreds of millions of individual virus particles. If you were to go in and pick out one virus at a time in this patient, you would find a range of mutations or variants in the mix. It’s a question of which ones have a growth advantage – that is, which ones can evolve because they are better than the original virus. Those are the ones that are going to become successful during the pandemic.

Of the mutations that have been detected, is one of particular concern?

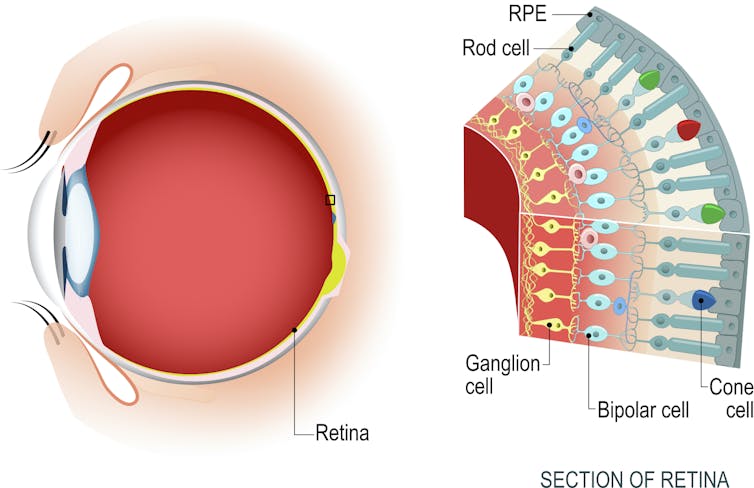

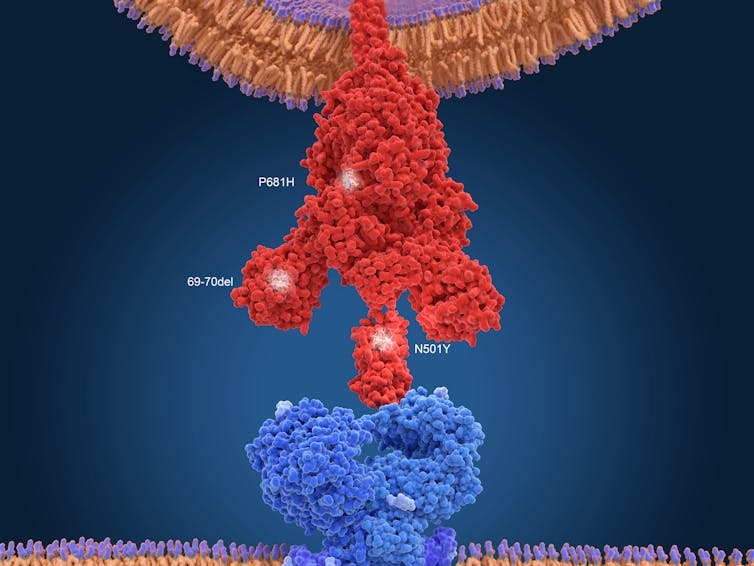

Any single variant or change in the virus is probably not that problematic. A single change in the spike protein – which is the region of the virus that attaches to human cells – is probably not going to be a big threat as the medical community rolls out the vaccines.

The current vaccines induce the immune system to produce antibodies that recognize and target the spike protein on the virus, which is essential for invading human cells. Scientists have observed the accumulation of multiple changes in the spike protein in the South African variant.

These changes allows SARS-CoV-2, for example, to attach more tightly to the ACE2 receptor and enter human cells more efficiently, according to preliminary unpublished studies. Those alterations could enable the virus to infect cells more easily and enhance its transmissibility. With multiple changes in the spike protein, the vaccines may no longer produce a strong immune response against these new variant viruses. That’s a double whammy: a less effective vaccine and a more robust virus.

Right now, the public doesn’t need to be concerned about the current vaccines. The leading vaccine manufacturers are monitoring how well their vaccines control these new variants and are ready to tweak the vaccine design to ensure that they will protect against these emerging variants. Moderna, for example, has stated that it will adjust the second or booster injection to more closely match the sequence of the South African variant. We’ll have to just wait and see, as more people receive vaccinations, whether the transmission rates will drop.

Why is lowering transmission key?

A drop in transmission rates means fewer infections. Less virus replication leads to fewer opportunities for the virus to evolve in humans. With less opportunity to mutate, the evolution of the virus slows and there is a lower risk of new variants.

The medical community needs to make a big push and get as many people vaccinated and thus protected as possible. If not, the virus will continue to grow in large numbers of people and produce new variants.

How the new variants are different

The U.K. variant, known as B.1.1.7., seems to bind more tightly to the protein receptor called ACE2, which is on the surface of human cells.

I don’t think we’ve seen clear evidence that these viruses are more pathogenic, which means more deadly. But they may be transmitted faster or more efficiently. That means that more people will be infected, which translates into more people who will be hospitalized.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

The South African variant, known as 501.V2, has multiple mutations in the gene that encodes the spike protein. These mutations help the virus evade an antibody response.

Antibodies have exquisite precision for their target, and if the target changes shape slightly, as with this variant – which virologists call an escape mutant – the antibody can no longer bind tightly, as it loses its power to protect.

Why do we need to monitor for mutations?

We want to make sure that the diagnostic tests are detecting all of the viruses. If there are mutations in the virus’s genetic material, an antibody or PCR test may not be able to detect it as efficiently or at all.

To be sure that the vaccine is going to be effective, researchers need to know if the virus is evolving and escaping the antibodies that were triggered via the vaccine.

Another reason that monitoring for new variants is important is that people who’ve been infected might be infected again if the virus has mutated and their immune system can’t recognize it and shut it down.

The best way to look for emerging variants in the population is to do random sequencing of the SARS-CoV-2 viruses from patient samples across diverse genetic backgrounds and geographical locations.

The more sequencing data researchers collect, the better vaccine developers will be able to respond in advance of major changes in the virus population. Many research centers around the U.S. and the world are ramping up their sequencing capabilities to accomplish this.![]()

Richard Kuhn, Professor of Biological Sciences, Purdue University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.