South African president Cyril Ramaphosa’s despatch of envoys to Zimbabwe in a bid to defuse the latest crisis, in which the government has engaged in a vicious crackdown on opponents, journalists and the freedoms of speech, association and protest, has been widely welcomed.

Such has been the brutality of the latest assault on human rights by President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s regime that something had to be done. And, as the big brother neighbour next door, South Africa is the obvious actor to do it.

It may be guaranteed that Ramaphosa’s envoys – Sydney Mufamadi, a former government minister turned academic, and Baleka Mbete, a former deputy president of South Africa, former speaker of the National Assembly and former chairperson of the African National Congress (ANC) – were sent off to Harare with a very limited brief. They were accompanied by Advocate Ngoako Ramatlhodi and diplomat Ndumiso Ntshinge.

The mission quickly ran into trouble. The envoys returned to South Africa without meeting members of the opposition.

Observers and activists are rightly sceptical about how much will come out of it. The best that is seriously hoped for is that South African diplomacy will bring about immediate relief. This would include: the release of journalists, opposition figures and civil society activists from jail; promises to withdraw the military from the streets; perhaps even some jogging of the Mnangagwa government to meet with its opponents and to make some trifling concessions.

After all, the pattern is now well established: crisis, intervention, promises by the Zanu-PF regime to behave, and then relapse after a decent interval to the sort of behaviour that prompted the latest crisis in the first place.

But in a previous era, South Africa once made Zimbabwe’s dependence count.

South Africa has done it once

Back in 1976, apartheid South Africa’s Prime Minister John B. Vorster fell in with US plans to bring about a settlement in then Rhodesia, and hence relieve international pressure on his own government, by withdrawing military and economic support and closing the border between the two countries.

Ian Smith had little choice but to comply. Today, no one, not even the most starry-eyed hopefuls among the ranks of the opposition and civil society in Zimbabwe, believe that Ramaphosa’s South Africa will be prepared to wield such a big stick. The time is long past that Pretoria’s admonitions of bad behaviour are backed by a credible threat of sanction and punishment.

So, why is it that Vorster could bring about real change, twisting Smith’s arm to engage in negotiations with his liberation movement opponents that eventually led to a settlement and a transition to majority rule, and ANC governments – from the time of Nelson Mandela onwards – have been so toothless?

If we want an answer, we need to look at three fundamental differences between 1976 and now.

First, Vorster was propelled into pressuring Smith by the US, which was eager to halt the perceived advance of communism by bringing about a settlement in Rhodesia which was acceptable to the West. In turn, Vorster thought that by complying with US pressure, his regime would earn Washington’s backing as an anti-communist redoubt. Today there is no equivalent spur to act. It is unlikely that US president Donald Trump could point to Zimbabwe on a map.

Britain, the European Union and other far-off international actors all decry the human rights abuses in Zimbabwe. But they have largely given up on exerting influence, save to extend vitally needed humanitarian aid (and thank God for that). Zimbabwe has retreated into irrelevance, except as a case study as a failed state. They are not likely to reenter the arena and throw good money and effort at the Zimbabwean problem until they are convinced that something significant, some serious political change for the good, is likely to happen.

Second, South African intervention today is constrained by liberation movement solidarity. They may have their differences and arguments, but Zanu-PF and the ANC, which governs South Africa, remain bound together by the conviction that they are the embodiments of the logic of history.

Read more: How liberators turn into oppressors: a study of southern African states

As the leading liberators of their respective countries, they believe they represent the true interests of the people. If the people say otherwise in an election, this can only be because they have been duped or bought. It cannot be allowed that history should be put into reverse.

Former South African president Thabo Mbeki played a crucial role in forging a coalition government between Zanu-PF and the opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) after the latter effectively won the parliamentary election in 2008. But South Africa held back from endorsing reliable indications that MDC leader Morgan Tsvangirai had also won the presidential election against Robert Mugabe.

As a result, Tsvangirai was forced into a runoff presidential contest, supposedly because he had won less than 50% of the poll. The rest is history.

Zanu-PF struck back with a truly vicious campaign against the MDC, Tsvangirai withdrew from the contest, and Mugabe remained as president, controlling the levers of power. The ANC looked on, held its nose, and scuttled home to Pretoria saying the uneasy coalition it left behind was a job well done.

Third, successive Zanu-PF governments have become increasingly militarised. Mnangagwa may have put his military uniform aside, but it is the military which now calls the shots. It ultimately decides who will front for its power. There have been numerous statements by top ranking generals that they will never accept a government other than one formed by Zanu-PF. The African Union and Southern African Development Community have both outlawed coups, but everyone knows that the Mnangagwa government is a military government in all but name.

Lamentably inadequate

So, it is all very well to call for a transitional government, one which would see Zanu-PF engaging with the opposition parties and civil society and promising a return to constitutional rule and the holding of a genuinely democratic election. But we have been there before.

The fundamental issue is how Zimbabwe’s military can be removed from power, and how Zimbabwean politics can be demilitarised. Without the military behind it, Zanu-PF would be revealed as a paper tiger, and would meet with a heavy defeat in a genuinely free and fair election.

According to Ibbo Mandaza, the veteran activist and analyst in Harare, what Zimbabwe needs is the establishment of a transitional authority tasked with returning the country to constitutional government and enabling an economic recovery. Nice idea, but a pipe dream.

No one in their right mind believes that a Ramaphosa government, whose own credibility is increasingly threadbare because of its bungled response to the coronavirus epidemic, its corruption and its economic incompetence, has the stomach to bring this about. We can expect fine words and promises and raised hopes, but lamentably little action until the next crisis comes around, when the charade will start all over again.

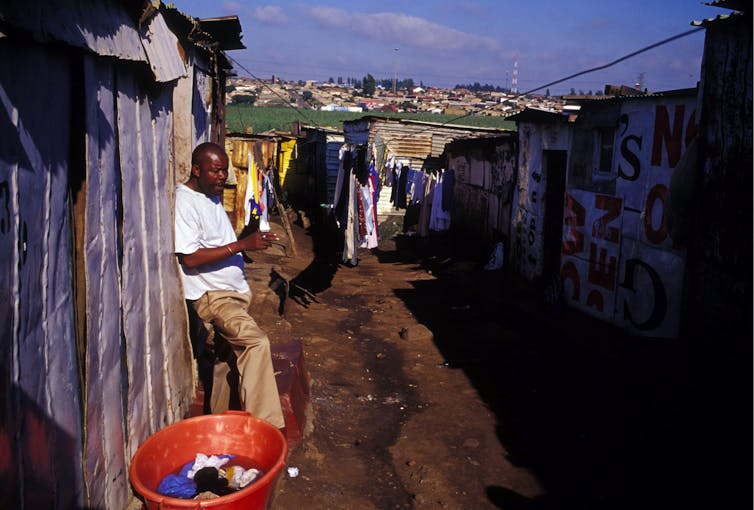

Any relief, any improvement on the present situation will be welcomed warmly in Zimbabwe. But no one in Harare – whether in government, opposition or civil society – will really believe that Ramaphosa’s increasingly ramshackle government will be prepared to tackle the issue that really matters: removing the military from power.![]()

Roger Southall, Professor of Sociology, University of the Witwatersrand

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.