For most of human history, people had access to food either by producing it themselves, or through trade.

Shutterstock

Fifty-four percent of South Africans are hungry or at risk of hunger. Hunger affects people’s health, as well as their ability to live full and productive lives. That’s why hunger represents a violation of their basic human rights – not only the right to food, but also the rights to dignity, health and education, since all of these are affected by hunger.

Hunger, malnutrition and related illnesses are not evenly spread. There are significant race, class and gender differences. For example, black South Africans are 22 times more likely to be food insecure compared with white South Africans. Food insecurity is defined as not having physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.

This unequal distribution indicates a situation of severe food injustice in South Africa. Yet from my research with urban farmers it’s clear that people do not know of the right to food, and don’t see unequal access to nutritious food as an injustice. As a result, questions of hunger are largely absent in South African politics. While there are frequent protests around access to jobs, education, housing, water and electricity, we rarely, if ever, see protests about access to food.

There are international examples of governments taking their obligations seriously with regard to the right to food. In the city of Belo Horizonte, Brazil, for example, the government has rolled out numerous food and nutrition security programmes to combat hunger. In India, activists used litigation to hold the government accountable, leading to the enactment of the National Food Security Act in 2013, and various anti-hunger programmes such as school meals, subsidised grain distribution and assistance to pregnant women.

South Africans could learn from these examples, and do more.

Food injustice

The concept of food injustice seeks to address issues of equity, fairness and control amid inherent inequality of the food system. Developed by researchers and activists in the US, it is equally relevant in South Africa, where centuries of oppression under settler colonialism and apartheid have created one of the most unequal societies in the world.

One of the drivers of unequal access to food is the way in which the industrial food system works. For example, a few large companies dominate each aspect of the food value chain.

This concentration means that smaller scale producers, processors and retailers are squeezed out. Because the large companies dominate the supply chain, they are able to maximise profits at the expense of small-scale producers, to whom they pay very low prices, and low-income consumers, who can’t afford the marked-up prices in shops.

The system has been normalised to the extent that it is rarely challenged.

In my study with urban farmers I asked participants about the right to food. The majority had never heard of it. Even when I explained the right, it was difficult for them to comprehend how it could work in the context of the current food system.

One woman in Bertrams, Johannesburg, challenged the concept:

A right to eat, but where will we get the food to eat? You’ll go to Spar [supermarket] and say, “I want to eat”, yet you don’t have money to buy food.

When asked if food manufacturers and retailers should help hungry people, another participant in Alexandra, said:

Yeah, I think they must help, but if they’ve got money. Because also they must get something and then they can manage to help people.

This view was expressed by a pensioner struggling to feed her grandchildren. On the other end of the scale might be the CEO of major retailer Shoprite, who earned R100 million (and additional incentives) in 2017 – 1332 times more than employees, who made R75,150.

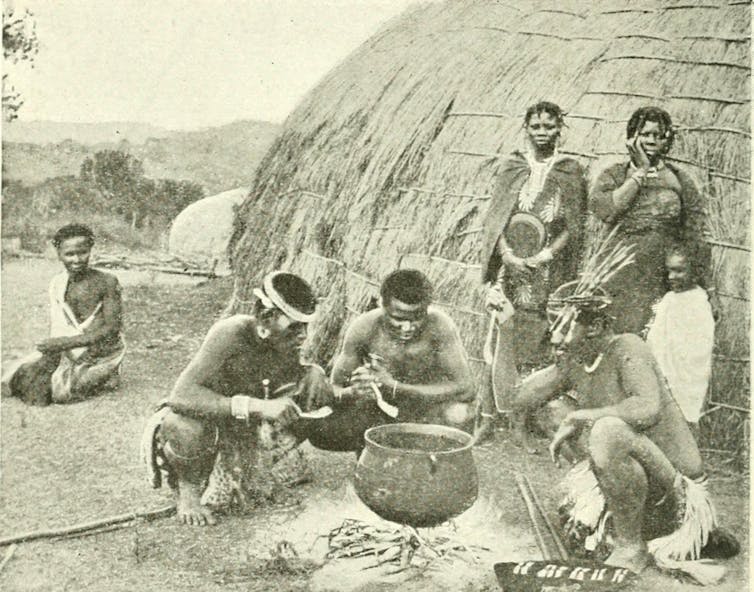

The idea of food being sold for profit has become entirely normalised. This is despite the fact that for most of human history, people had access to food either by producing (or gathering) it themselves, or through trade. Some of the older participants in the study actually experienced this during their childhoods in rural areas. Their households were largely self-sustaining – growing crops, raising livestock, and sharing or trading with neighbours as needed.

Many of the research participants had monthly household food budgets of around R450 per person per month. At this rate, a healthy diet is simply unaffordable. The Pietermaritzburg Economic Justice and Dignity Household Affordability Index suggests that the cost of a basic nutritious food basket for a family of four is R2,327.17 (or R581.79 per person).

Realising the right to food

Tackling food injustice requires a transformation of the structural inequities of the food system. It needs to ensure that marginalised producers, processors and retailers have an opportunity to earn a decent living. At the same time corporate dominance needs to be addressed.

To break the cycle of poverty and malnutrition, the government also needs to ensure that children have access to sufficient, healthy food. This might entail food provision linked to pre- and post-natal care, as well as provision of healthy meals at early childhood development centres.

It requires providing alternative means to access healthy food. This could be through access to land and water, or through subsidised fresh produce and healthy meals. Programmes such as those in Brazil or in India provide examples of how government interventions (through subsidies and distribution) can improve access to food.

At the most basic level, it requires that South Africans know they have a right to food in the first place.

Eight years ago the then UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, Olivier de Schutter criticised South Africa’s progress on this score and made a number of recommendations for improvement. Sadly, little has changed. It’s time South Africans demanded government action.

Brittany Kesselman, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, University of the Witwatersrand

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.