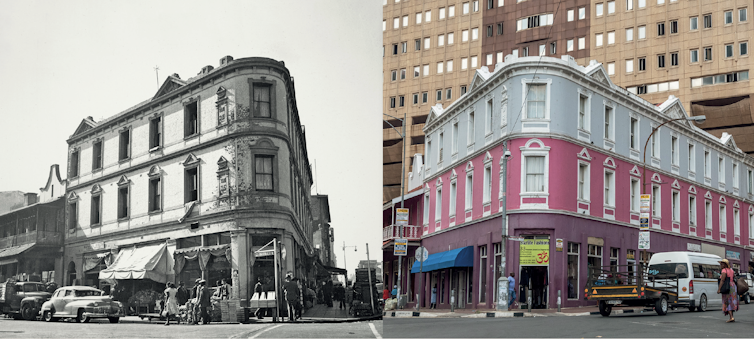

Cyril Ramaphosa’s economic stimulus package shows that he and his political allies are in charge of economic policy.

GCIS

The economic stimulus package announced by South African President Cyril Ramaphosa shows that he and his political allies are, contrary to much analysis in recent months, in charge of economic policy.

Ramaphosa insists that it is a ‘bold’ attempt to initiate economic change which will particularly benefit youth, women and small businesses. It rests partly, he adds, on ‘significant regulatory reform’.

But the package is more interesting for what it says about the politics of economic decision-making in South Africa’s governing African National Congress (ANC) than for its likely impact on the economy.

Certainly, it does not signal readiness by Ramaphosa and his allies to use their power to introduce much-needed reforms. In an article in the financial press explaining the thinking behind the package, Ramaphosa acknowledged that it rested not on new ideas but on trying to get the government to do what it has already said it will do. He wrote that it was “tempting to unleash novel policy directions” but it was far more important “to build a track record of successful implementation.”

Much of the package depends, therefore, on trying to ensure that government lives up to commitments it has already made – on, for example, funding infrastructure and allocating broadband spectrum licenses – rather than striking out in a new direction.

It is hardly surprising, then, that critics to the President’s left complain that there is no change in the government’s market-friendly approach. Indeed, a business chamber noted that it repeated much that the government had been promising to do over the past five years. The package does not depart from the policy framework which has guided government thinking on the economy for more than two decades.

This might make it seem like a non-event. In reality, the background to the package means that it is politically important.

Timing

The package’s details were announced in late September two months after Ramaphosa first

announced it was on the way. At the time, he also revealed that the ANC had changed its mind and would seek a constitutional amendment to allow it to expropriate land without compensation, having previously insisted that it did not need to change the constitution to do so. Both announcements followed a meeting of the ANC’s national executive committee which makes decisions between conferences. This strongly suggested that the national executive committee had insisted on both the land and the stimulus decisions.

This seemed to send an important message on the balance of power within the national executive committee on economic issues - that Ramaphosa and his allies had been caught off guard by supporters of former president Jacob Zuma.

Ramaphosa narrowly won the ANC presidency whose leadership, including the national executive committee, is divided almost evenly between his supporters and those who backed Zuma. His backers, who are inclined towards a market economy approach, are opposed to the patronage politics of Zuma’s faction, which has come to be associated with corruption and ‘state capture’ (using government for personal enrichment).

Ramaphosa’s chief mandate was to tackle corruption and ‘state capture’ and it was assumed that the Zuma group would try to stop him. But his opponents seem to have shifted their strategy. Instead of, as expected, complaining that anti-corruption measures were doing the bidding of white-owned corporations, they demanded change on policy issues such as land. This seemed to have wrong-footed Ramaphosa and his supporters, forcing them to react rather than to steer the ANC’s agenda.

The stimulus package seemed to stem from the same source as the land announcement – a push by the Zuma group to shape economic policy. All of this suggested that the Zuma faction was successfully pushing ANC policy in a less market-friendly direction.

But the fact that the package is firmly within the current framework signals clearly that Ramaphosa and his supporters are, after all, in charge of economic policy. It shows that they decide the government’s response to economic challenges despite the Zuma faction’s strong presence.

This does not mean that they are directing the ANC and government economic agenda. They still seem to be reacting to pressures for policy change from their rivals.

This is not surprising. Poverty and inequality are still strong realities in South Africa and many black professionals and business people still believe that they do not enjoy equal opportunities. If Ramaphosa and those who agree with him simply dismiss the calls for change, they will appear to be defending the indefensible. This allows its opponents to insist on government action – but they do not control the details when the decision to take action is turned into a concrete policy or programme.

That they were able to decide the details of the stimulus package is important if we bear in mind that the economy is in recession, which should increase pressure for more government spending – a pressure which they resisted. And, if they are able to shape the details of the stimulus package, it seems likely that they are equally able to shape policy changes on land and other issues, such as national health insurance, which are likely to be sources of pressure for change in the near future.

What is not clear is whether they are able to decide what will change – rather than just react to what their opponents want. To do this, they need to move beyond their current framework and to seek to take the economy in a new direction, which would tackle the exclusion of millions from its benefits while preserving, and strengthening, its ability to produce.

Need for a new path

It is now widely agreed that a new path is needed. Ramaphosa’s group will, therefore, remain on the defensive as long as the voices insisting that change is needed are those of their opponents. There is no contradiction between taking seriously the need for growth and investment and steering the economy in a direction which will open opportunities for many more people. On the contrary, the one depends on the other.

Given this, the voices calling for change – as well as those deciding what form it should take – should be those of the faction which insists it wants to get the economy working for all. It should not wait for the group which sees calls for radical change as a means of siphoning off the public’s resources to a small group of connected people to place the need for change on the government’s agenda.

Steven Friedman, Professor of Political Studies, University of Johannesburg

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.