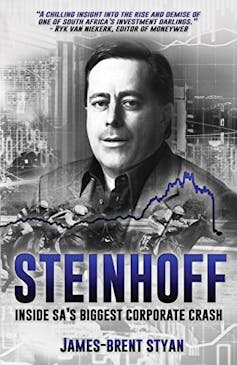

Steinhoff CEO Markus Jooste was an excessively dominant, forceful and feared boss.

shutterstock

The collapse of Steinhoff International, the multi-billion dollar global business group, has been rightly described as the biggest corporate scandal in South African history.

The company’s history, and its subsequent evolution and demise, are skillfully told in a new book Steinhoff: Inside SA’s Biggest Corporate Crash, by former journalist James-Brent Styan. It is the story of a bold vision and ambition, entrepreneurial grit and guile, continuous innovation, relentless risk-taking, corporate hubris, and friendship betrayals.

The extraordinary way in which Steinhoff grew from being a modest firm with a footprint only in Germany and South Africa to becoming a multinational behemoth straddling sectors such as furniture manufacturing, retail, logistics, consumer finance, building material, wood and vehicles with a global presence, is impressive.

In its pursuit of growth, Steinhoff employed a two-pronged strategy. The first focused on creating a low-cost manufacturing base. This enabled the business to supply products at cheap prices to its target market of lower-to-middle income groups.

The second pillar consisted of an aggressive acquisition of companies. A great deal of the acquisitions took place in European countries such as Germany, Poland and France but also extended to Australia, New Zealand, Britain and the US.

The acquisitions were costly and the conglomerate paid above the market value for the shares. The rapid spate of takeovers saw the group expand to 12 000 stores across the world, employing 130 000 people. Ultimately, Steinhoff became a fully vertically integrated enterprise – it was involved in all the value chain links from sourcing raw materials, to manufacturing and finally to distribution and sale of products.

Shaky foundations

At the pinnacle of its success, the international business giant became the darling of investors, asset managers, analysts and financial journalists. They all feted its expansion into new ventures and countries. But, as it later turned out, its success was built on shaky foundations epitomised by unfettered greed as well as dodgy and unethical practices, including alleged accounting irregularities, tax evasion and lax corporate standards.

The day before the Steinhoff group’s precipitous crash, the corporation was worth R193bn. On the following day, its market value was decimated by a staggering R117bn. Among the victims of the financial carnage were financial South African services giants Coronation Fund, Foord Asset Management, Sanlam, Investec, Liberty, Old Mutual, Allan Gray, Discovery and the Nedgroup.

The biggest losers were key investor and Pepkor chairman Christo Wiese (R37bn) and the Public Investment Corporation (R14bn), which manages the Government Employees Pension Fund. Overnight, millions of South Africans had lost billions of rands in pension funds.

The book encompasses a diverse range of themes and proffers a number important business lessons. Some bear mentioning.

Lessons

The case of Markus Jooste, then Steinhoff CEO, shows that the cult of personality and “Big Man” syndrome is as ubiquitous in the corporate world as it is in politics. He comes across as an excessively dominant, forceful and feared boss. He brooks no dissent and only those subordinates who obsequiously defer to him benefit from his extensive patronage. To the detriment of the business, his leadership style fostered an institutional culture of uncritical subservience and self-censorship.

A recurring question in the book is: Despite occasional red flags how could the analysts, investors, asset managers, directors and the Johannesburg Securities Exchange have been oblivious to the wrongdoing at Steinhoff?

Part of the problem was the dominant view that the company could never go wrong. As long as the share price kept rising, and the good news kept flowing, there was nothing to worry about. There were, of course, some skeptical and dissenting voices, but they were too few to upend the prevailing consensus.

The crucial lesson here is that the share price is not the only indicator of corporate performance; fundamental governance issues are equally, if not more, important.

As Steinhoff’s global expansion accelerated, its business model and structure became more complicated. Some market analysts have argued that the firm’s increasingly complex structure, coupled with the group’s continual acquisitions, made it nearly impossible to analyse its books and to do year-on-year comparisons.

Even so, there was a belief that as long as strong, charismatic and venerated business personalities such as Jooste and Wiese, Steinhoff’s chairman at the time, were at the helm the business was in safe hands. This trust in Jooste and Wiese, as well as in management and directors, proved to be misplaced. As Warren Buffett has wisely counselled, never invest in something you don’t trust.

The Steinhoff board of directors, long viewed as one of the strongest and most dependable, has come under fierce criticism for failing to exercise its fiduciary duty. Describing the board, one fund manager stated that it was

“ineffective, not independent and was overwhelmed by Jooste’s strong personality”.

Criticism has also been directed at Deloitte, the firm that audited the company’s statements for 20 years, for disregarding the irregularities and the danger signs preceding the crash. It is this milieu that prompted an analyst to describe what happened at Steinhoff in the book as follows:

It’s a buddy-buddy system, a bunch of people who know each other and have worked together for years. It strips them of their capacity to question things that don’t make sense.

Up there with the worst

Styan must be commended for producing a cogently written and thoroughly researched book. In terms of its drama and catastrophic impact, the Steinhoff scandal is up there with the likes of Enron, Worldcom, Tyco, Freddie Mac, Bernie Madoff and other world infamous episodes of business malfeasance. As such, the book provides valuable insights and lessons that are universally applicable and comparable. It must be made compulsory reading in corporate boardrooms and business schools.

Mills Soko, Associate Professor, Graduate School of Business, University of Cape Town

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.