The flaws in the political settlement that ended apartheid need urgent attention.

GCIS

If he were alive today, Nelson Mandela would probably be puzzled to find that it has become popular among South Africans frustrated with the pace of change to join former Zimbabwean president Robert Mugabe in casting him as a villain.

The charge against Mandela, who became South Africa’s first democratically elected President on May 10 24 years ago, is that he let white South Africa off the hook by bargaining a deal which left the racial minority in charge of the economy and society. His reconciliation policy, it is claimed, made whites feel good but did little for blacks.

How justified is this? Should South Africans blame Mandela for the survival of racial bias, poverty and inequality? Or does he remain an inspiration? The answer lies somewhere in between these two poles.

Before explaining why, it’s as well to warn against the tendency to see apartheid’s end as Mandela’s work alone. As he never tired of pointing out, he was part of a collective: key strategic roles were played by former president Thabo Mbeki and the country’s current leader Cyril Ramaphosa, among many others. This week 24 years ago saw the beginning of democratic government, not rule by one man.

Whether Mandela and his colleagues could have done better depends on what their critics think they should have done. If the answer is that they should have insisted on far more radical change, how were they to achieve this since the apartheid system was not defeated militarily? And how was the new order to feed its people if it frightened away the capital which remained in the white minority’s hands?

Missed opportunity

Mandela’s reconciliation message may have partly reflected his view of the world. But it was also a product of the African National Congress’ (ANC) view then that the minority retained the power to destroy the new democracy and so a compromise with it was essential.

This sometimes led to skewed priorities. Preventing a white backlash was at times taken more seriously than black opinion outside the ANC which was also not sure about the new order. But the ANC’s view that apartheid could only be ended by a compromise was, essentially, accurate. Those who continue to complain that Mandela and his colleagues settled for far too little have never said credibly how it would have been possible to get much more.

Critics are right to insist that something was missing from the settlement which made Mandela president. But the problem is not that there was too much compromise; it was that there was not enough.

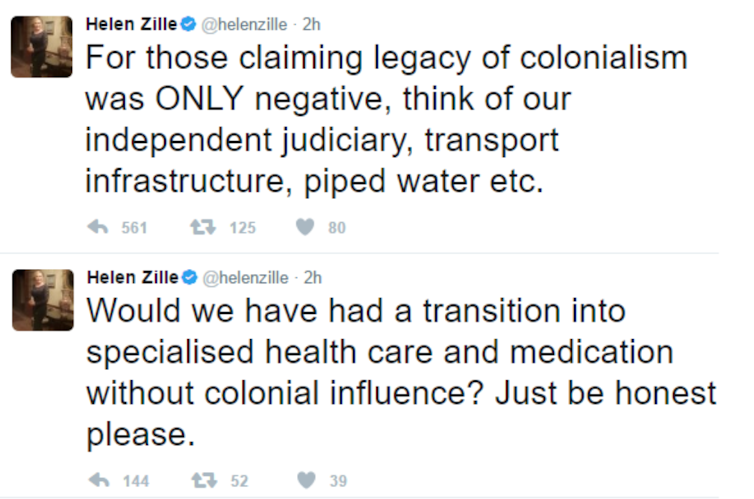

The compromise which produced 1994 concentrated on changing the political order so that everyone became a citizen with equal rights. That was essential. But it left untouched an economy, society and culture which, like the political system, worked only for the few. The political bargain should have been followed by a similar negotiation on opening up the economy. It should also have tackled the biases in the places where ideas and knowledge are produced - schools and universities, for example, and those in the wider society where inherited privilege in access to health care, transport and other essentials have limited the effects of the political changes Mandela and others achieved.

This was a missed opportunity because the years leading up to the settlement which produced the 1994 democratic government saw parallel negotiation on the economy, social issues and education and culture. This could have set the stage for a bargain on change in these areas but the opportunity was ignored. This has produced the bitterness that sees Mandela as a problem, not a solution.

This flaw needs urgent attention. Unless it is addressed, South Africa will remain what it is today: angry and fractured, still trapped in many of the chains which apartheid created. Mandela and those who worked with him hoped for more – a society in which the old barriers would break down, not one in which they remain, although on new foundations. What they hoped for has not been achieved partly because they failed to find a strategy for addressing the ills apartheid created.

Building a new society

But the new society for which they hoped will not be created unless the values which they championed at the time are revived. The message that South Africans share a common humanity is not a sham. It is essential in a society which remains deeply divided. It does not mean ignoring inequalities: it makes it essential that they are tackled, but in a way which recognises what people hold in common.

The spirit of self-sacrifice and service which prompted Mandela and others to fight apartheid and seek to build a new society is equally essential in a country in which how much you own is valued more than how much you contribute, one of the many causes of corruption which continues to scar the country.

Steven Friedman, Professor of Political Studies, University of Johannesburg

This article was originally published on The Conversation.