Shutterstock

South Africa’s governing party, the African National Congress (ANC), recently adopted a resolution to nationalise the country’s central bank. The move comes on the back of calls for government to rein in the South African Reserve Bank, causing concerns that the bank’s independence will be lost. Sibonelo Radebe asked Jannie Rossouw to consider what’s at stake.

What do you make of the ANC’s resolution?

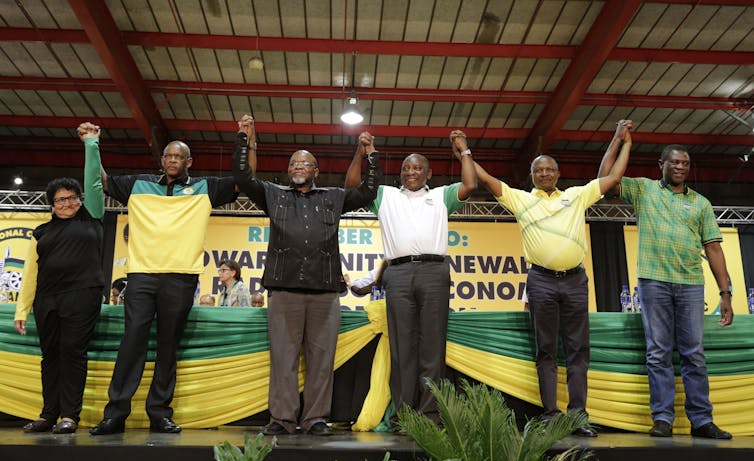

The ANC’s thinking around this resolution is a bit ambiguous and confusing. The resolution itself and subsequent comments by the new ANC President, Cyril Ramaphosa, say that the resolution should not affect the independence of the bank.

While upholding the resolution to nationalise, Ramaphosa added this qualification:

The Reserve Bank plays a critical role in the life of any nation with regard to monetary policy and safeguarding and promoting the value of its currency. The ANC once more reaffirms the role, mandate and independence of the Reserve Bank.

He clearly wants to protect the central bank from political interference. This should be welcomed because political interference would have an impact on the constitutional mandate of the central bank.

But those pushing for nationalisation are against it remaining independent from political interference. They want its independence curtailed. This view is aired by those on the left in the ANC, such as the Congress of South African Trade Unions and the South African Communist Party. They believe that the Reserve Bank is misguided on focusing on keeping inflation under control and that this compromises economic growth. Prominent ANC leaders have also backed this view.

On its own, a change of the bank’s ownership from private shareholders to the South African government wouldn’t affect the constitutional mandate of the central bank. Government ownership doesn’t automatically imply government control. This is evident in countries like the UK, Sweden and Denmark, where government ownership of central banks doesn’t affect their unwavering commitment to keep inflation under control.

How does this resolution fit into global trends?

Nationalisation would align the South African Reserve Bank’s ownership structure with the majority of central banks across the world. Other than in South Africa, central banks with private shareholders can be found in seven other countries. These are Belgium, Greece, Italy, Japan, San Marino, Switzerland and Turkey.

The number of central banks with private shareholders have declined over the years since the nationalisation of the Reserve Bank of Zealand. Many more countries followed. The most recent was the National Bank of Austria in 2010.

What influence and benefits do the shareholders of the bank have?

The South African Reserve Bank has 2 million issued shares, held by the general public, which includes individuals and juristic persons. No group of shareholders (referred to as associates) can hold more than 10 000 shares. This ensures that no shareholder can exercise undue influence over the activities of the bank.

Shareholders in the Reserve Bank have very limited powers. And being a shareholder isn’t very lucrative. They are entitled by law to annual dividends not exceeding 10c per share per annum, which amounts to 8c per share after tax.

Shareholders also have the right to attend the bank’s ordinary annual general meeting where they are able to approve the appointment of the external auditors of the bank and set their remuneration. They also elect six of the 13 board members. The other board members, including the Governor and the deputy governors, are appointed by the president of the country.

The board plays an oversight role on the governance of the bank – including being responsible for the bank’s annual financial statements. But its mandate does not extend to monetary policy decisions.

This structure of general meetings adds an additional layer of transparency to the activities of the central bank and improves its accountability. At general meetings (which are also attended by journalists), the Governor answers questions on the bank’s activities and on its financial performance. The whole process adds to the transparency and general understanding of the role and activities of the central bank.

What needs to happen to give effect to the ANC resolution?

The nationalisation of the bank will require an amendment to the South African Reserve Bank Act which stipulates the private shareholding. Amendments require a simple majority in parliament.

Nationalisation could therefore happen as soon as legislation is prepared and a bill is passed in parliament.

But the process could become far more complex if nationalisation trampled on some international interests that are anchored in international treaties. At the moment it’s not clear whether or not this is the case.

The other challenge might be around determining the buyout value of the bank’s shares. This is because the South African Reserve Bank Act makes provision for the liquidation of the central bank, but not for its nationalisation.

In the event of liquidation, the legislation prescribes that shareholders should be reimbursed for their shares in terms of a formula based on the trading value of these shares. The shares are traded on an over the counter share trading platform. The last traded price per share was R9,60.

A different approach could be to use the share price confirmed by the High Court in dealing with delinquent shareholders. The central bank had to approach the High Court to deal with shareholders who failed to adhere to legal prescriptions in respect of maximum of 10 000 shares held by associated shareholders. In this instance the High Court confirmed a price of R1,55 per share which was calculated by consultant firm KPMG on behalf of the central bank.

Jannie Rossouw, Head of School of Economic & Business Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand

This article was originally published on The Conversation.