Cyril Ramaphosa, the new president of South Africa’s governing party, the ANC, and potentially the country’s future president.

Reuters/Siphiwe Sibeko

Rumours that President Jacob Zuma has instructed the South African National Defence Force to draw up plans for implementing a state of emergency may or may not be true. Nonetheless they are evidence of South Africa’s febrile political atmosphere.

But any assumption that the election of Cyril Ramaphosa as the new leader of the African National Congress (ANC), after winning the race against Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, will place South Africa on an even keel are misplaced. Indeed, the drama may only be beginning.

It’s useful to look back to 2007 when President Thabo Mbeki unwisely ran for a third term as ANC leader. His unpopularity among large segments of the party provided the platform for his defeat by Zuma at Polokwane. Within a few months the National Executive Committee of the ANC latched onto an excuse to ask Mbeki to stand down as president of the country before the end of his term of office. Being committed to the traditions of party loyalty he complied, resigning as president some eight months before the Constitution required him to do so.

The question this raises is whether South Africa should now expect a repeat performance following the election of a new leader of the ANC. Will this lead to a party instruction to Zuma to stand down as president of the country? And if it does, will he do what Mbeki did and meekly resign?

There’s a big difference between the two scenarios: Mbeki had no reason to fear the consequences of leaving office. Zuma, on the other hand, has numerous reasons to cling to power. This is what makes him, and the immediate future, dangerous for South Africa, and suggests the country faces instability.

Why Zuma won’t go

It is not out of the question that Zuma may say to himself, and to South Africa, that he is not going anywhere. He is losing court case after court case, and judicial decisions are increasingly narrowing his legal capacity to block official and independent investigations into the extent of state capture by business interests close to him.

With every passing day, the prospects of his finding himself in the dock, facing 783 charges, including of corruption and racketeering, also increase.

Zuma will have every constitutional right to defy an ANC instruction to stand down as state president until his term expires following the next general election in 2019, and the new parliament’s election of a new president. In terms of the South African Constitution, his term of office will be brought to an early end only if parliament passes a vote of no confidence in his presidency, or votes that, for one reason or another, he is unfit for office.

But today’s ANC is so divided that it cannot be assumed that a majority of ANC MPs would back a motion of no confidence, even following the election of Ramaphosa as the party’s new leader.

In other words, there is a very real prospect that South Africa will see itself ruled for at least another 18 months or so by what is termed “two centres of power”, with the authority and the legitimacy of the party (formally backing Ramaphosa) vying against that of the state (headed by Zuma).

Throwing caution to the wind

As if that is not a sufficient condition for political instability, we may expect that Zuma will continue to use his executive power to erect defences against his future prosecution. He will reckon to leave office only with guarantees of immunity. Until he gets them, Zuma will defy all blandishments to go. And if he does not get what he wants, he may throw caution to the wind and go for broke.

Hence, perhaps, the possibility that he is prepared to invoke a state of emergency.

The grounds for Zuma imposing a state of emergency would be specious, summoned up to defend his interests and those backing him. They would be likely to infer foreign interference in affairs of state, alongside suggestions that white monopoly capital, whites as a whole as well as nefarious others were conspiring to prevent much needed radical economic transformation. Present constitutional arrangements would be declared counter-revolutionary and those defending them doing so only to protect their material interests.

After a matter of time, such justifications would probably be declared unconstitutional by the judiciary. It is then that there would be a confrontation between raw power and the Constitution. If such a situation should arise, we cannot be sure which would be the winner.

South Africa’s army

It is remarkable how little the searchlight that has focused on state capture has rested on the Defence Force. Much attention has been given to how the executive has effectively co-opted the intelligence and prosecutorial service, as well has how the top ranks of the police have been selected for political rather than operational reasons.

It seems to have been assumed that South Africa’s military is simply sitting in the background, observing political events from afar. But is it? Where would its loyalties lie in the event of a major constitutional crisis?

The danger of the present situation is that South Africa might be about to find out.

Were the military to throw its weight behind Zuma the country would be in no-man’s land. Of course, there would be a massive popular reaction, with the further danger that the president himself would summon his popular cohorts to “defend the revolution”.

And South Africans should not assume that Zuma would be politically isolated. Those who backed Dlamini-Zuma did so to defend their present positions and capacity to use office for personal gain. If they were to rise up, the army would then be elevated to the status of defender of civil order.

What is certain is that in such a wholly uncertain situation the economy would spiral downwards quickly. Capital would take flight at a faster rate than ever before, employment would collapse even further, poverty would become even further entrenched.

Reasons to be hopeful

Is all this too extreme a scenario? Hopefully yes. There are numerous good reasons why such a fate will be averted.

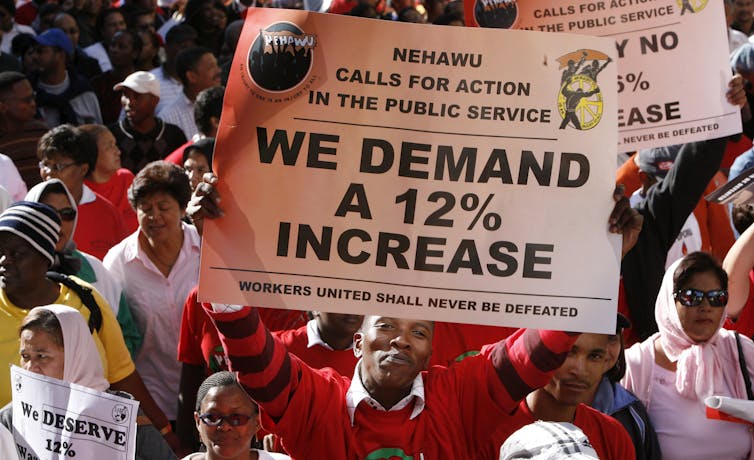

Zuma’s control over the ANC is waning, as is his control over various state institutions, notably the National Prosecuting Authority. And the country has a checks and balances in place: there is a vigorous civil society, the judiciary has proved the Constitution’s main defence and trade unions and business remain influential.

Roger Southall, Professor of Sociology, University of the Witwatersrand

This article was originally published on The Conversation.