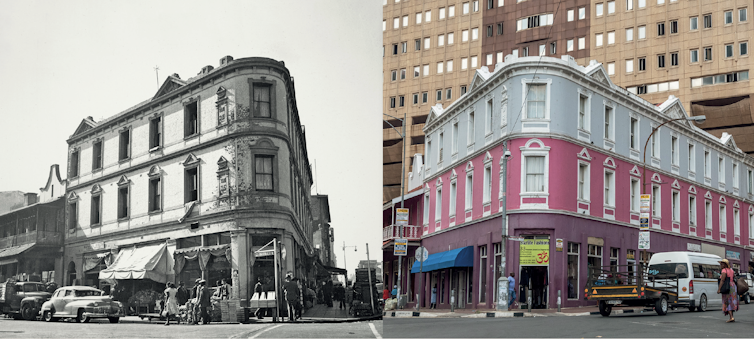

Carmel Building in Diagonal Street, Johannesburg.

Museum Africa (left) Yeshiel Panchia (right)

Johannesburg was always a much photographed place from its earliest days. It was a city that grew up with photographers and their cameras. As a town of migrants and immigrants, people wanted to send postcards and photographic souvenirs back home.

Some proof is in a new book, Johannesburg Then and Now, by history blogger, Marc Latilla. It is a series of photographic juxtapositions of early photographs of the city – dating from the 1880s to the 1940s – with contemporary images of the same street scene or building by photographer Yeshiel Panchia.

The book is descriptive rather than analytical, with the emphasis on Johannesburg buildings, places and streets and not its people. Latilla’s love and passion for his city comes through in his descriptions.

Young city

At a mere 132 years Johannesburg is a young city compared with cities of the world. London and Rome go back over 2000 years.

It started as a mining camp with a gold bonanza once George Harrison had found gold on the Main Reef in 1886. The new mining settlement was named Johannesburg – the origins of the name and who precisely was the “Johannes” of Johannesburg is still in dispute. The camp grew over time to a city. Today it is a metropolis that dominates the province of Gauteng, both as the provincial capital and the financial heartland of South Africa.

Johannesburg is a fractured city, divided in all sorts of ways. Geographically it’s split by the mines of the Witwatersrand - one can still see their remains south of the city while the north has a very different landscape.

Another divide was created by the railway which cut the town in half with the most affluent suburbs to the north and the less affluent to the south.

The city’s economic divide was also evident in the architectural styles of the residential areas which reflected status: from the working class, to the lower and upper middle class, and then at the very top end the grand estates on the northern ridges for the Randlords and newly enriched capitalist class.

The town was also divided by race from its earliest days. While there was always economic integration, segregated residential areas for different racial groups were the norm. The township of Soweto was created in the 1930s when the white government started separating black people from white people.

This policy of racial and class separation was perpetuated further when apartheid became official policy in 1948. It also led to forced removals of black people to townships outside the “white” city.

Growing in circles

Johannesburg has always grown in concentric circles. Municipal boundaries were periodically extended, mapped and basic services of water, sewerage, lighting, tramways financed by an increasing number of ratepayers brought into the net to support the city. Soweto, once the internationally recognised site of the 1976 youth uprising, is now part of the city, but so is the glitzy new glass and concrete post-modern city of Sandton.

The Johannesburg that has been captured in this book though is the old Johannesburg; what was called the Central Business District and its surrounding suburbs. This is Johannesburg from 1886 to a date more or less 50 years later when the city celebrated its jubilee with the Great Empire exhibition at Milner Park in 1936.

I should declare an interest – I was first asked by Penguin Books if they could use an image of an old early title deed that I had written about and then to give the book a preliminary early opinion. As historian I found myself drawn in to assist in some fact checking and comments to help the author. Of course the selection of photographs and his commentary remain his entirely.

The old photographs were taken by countless unknown and mainly anonymous photographers. They are remarkable in their own right. It was so much more difficult to take and make a photograph in 1900 than in our digital age. Those old photos in black and white are works of art as much as are the perfect colour and light reflected images of today. The sources of the old photographs are primarily from collections held by the University of the Witwatersrand, Museum Africa and the Transnet Heritage library. The early photographs are tend to be undated, so that the “then” can be any time from circa 1890 to the 1930s and even later, while the now photographs are all in colour and clearly belong to the last few years.

Superb find

My favourite photo is the old aerial view of the Harrow Road redevelopment when the first Johannesburg freeway was engineered (Harrow has since been renamed after a famous Johannesburger, the liberation struggle stalwart Joe Slovo). The photo allows us to see precisely how Harrow Road was widened and changed direction in the fifties. This single photo is a superb find.

A book such as this makes a contribution to heritage because it captures, assembles and documents the old and now the new. Where old photographs have been found recording what a particular building looked like and the building is still there, such photographic documentation strengthens the heritage preservation case.

However, none of the grit, crime, grime, litter or lack of maintenance we battle against today is visible in the modern photographs. This is the Johannesburg we don’t see: the crisis of homelessness and densification of dwellings. Who, for example, would know in the photo of Plein Street park that it is actually now a dormitory area for dozens of homeless people without jobs? Is it the city or history or harsh economic realities that has failed them? Of course one can argue that modernization and urbanization always left victims and the city of gold did not bring fabled wealth to all .

Johannesburg Then and Now is a fascinating book. It’s important for cities to preserve their pasts , because “Roots” matter as much as “shoots”. This book can perhaps start a discussion about what ought to be appreciated and “saved”. The book will remind city planners to include heritage in their planning for a 21st century city.

Johannnesburg Then and Now is published by Penguin.

Kathy Munro, Honorary professor in the School of Architecture and Planning, University of the Witwatersrand

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.